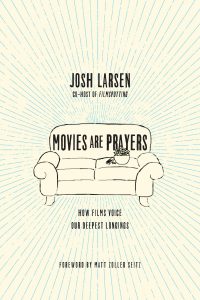

by Josh Larsen.

IVP Books, 2017.

Paperback, 208 pages, $16.

Reviewed by Mark Judge

Film critic Josh Larsen has written a beautiful and grace-filled book. Movies Are Prayers got strong reviews in the Christian media when it was released last year, but was mostly ignored in the secular press. This is unfortunate, as Larsen’s book has great insights into film that can make sense to film fans across the board, if not to hard-core leftist academics and their counterparts, conservative ideologues who narrowly see left-wing propaganda in nearly every film and champion garbage movies like the 2018 Death Wish remake because it irritates liberals.

In Movies Are Prayers Larsen’s thesis is that human beings are by nature praying creatures. Even before the establishment of official religions, we expressed praise, gratitude, anger, appreciation, and disillusionment to an unseen force. Using the theory of common grace, which is “this notion that an agnostic artist, by God’s favor, can capture the glory of his creation,” Larsen argues that artists and filmmakers are constantly offering gestures of prayer in their art, even without knowing it or naming it. “Prayer can be an unconscious act, one guided by the Holy Spirit as much as our own script,” Larsen writes, citing Romans 8:26. “Even the howl of an atheist,” he adds, “is directed at the God they don’t acknowledge.”

Larsen explores nine expressions of prayer that are found in movies—prayers of praise (creation), prayers of yearning, lament, and anger (fall), followed by prayers of confession, reconciliation, obedience, and meditation/contemplation (redemption), and ending with prayers of joy (restoration). Larsen is convincing in each of his examples, although I found that the chapter on film as praise most beautifully lays out his case. Larsen starts with Avatar, the 2009 James Cameron blockbuster that was derided by conservatives as being an anti-military spectacle of New Age earth-worship. Pandora, the eye-popping world Cameron created, is teeming with life—as Larsen observes, “life on this alien world gallops and grows, swoops and streams … feathery, spiral plants as tall as cars instantly shrink at the slightest touch. Bioluminescent seeds drift in the air and gently settle on branches, looking like landlocked jellyfish. Even the ground is alive.”

Teeming is the word Larsen uses to describe this world, noting that it is the same word used in both Genesis and the Psalms to describe the vast life-force of the sea. Quoting Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann—“praise is not only a human requirement and a human need, it is a human delight”—Larsen convincingly argues that Avatar is not liberal propaganda but a holy work of pop art. (Larsen also examines The Tree of Life, Terrence Malick’s 2011 spiritual meditation on the creation of the world.)

Larsen then moves to Breathless, the 1960 film by Jean-Luc Goddard that was seminal in the French new wave of cinema of the 1950s and 1960s. Breathless, a crime drama featuring quick jump cuts and shot on a hand-held camera, seems the opposite of the CGI extravaganza Avatar. Yet in Breathless Larsen also sees the delight of creation: “If there is a common feature to most of the film in French New Wave—a frame that keeps this oddly reconfigured puzzle together—it is playfulness.” The French New Wave was not a rupture from previous cinema but a happy evolution of what came before. Again and again Larsen touches on the theme of praise not as rote and memorized prayers, although as a Christian Larsen sees the value of those expressions, but as happiness, joy, and delight. These are three things that the best films, movies like The Wizard of Oz, Breathless, Star Wars, E.T., Smokey and the Bandit, and the recent Marvel popcorn movie Ant-Man and the Wasp, deliver.

I recently wrote in the University Bookman about my own experience working in a movie theater in the 1980s, and another story from that time serves to bolster Larsen’s argument. When I first got hired it was the beginning of the summer and the manager asked me to come in early to fill out some paperwork. The theater, the Bethesda Cinema ’n’ Drafthouse, was an art deco jewel that had been converted into a cavernous hall where patrons could watch films, drink beer, and eat pub food. (The theater is now a blues and jazz club.)

When I arrived it was a brilliantly sunny day and the first showing was not until that night. I came through the lobby and into the theater. There was a film playing, the soft erotic drama 9 1/2 Weeks, a private screening for only one person—the manager, my new boss. I recall this so vividly because the moment was charged with such spiritual energy. I had moved from the bright outside world into a kind of temple. The silhouette of my boss against the dreamy images onscreen looked like a pilgrim sitting in a church pew, sort of like the scene when the dissolute filmmaker in Cinema Paradiso returns home and watches the final reel his blinded mentor, who ran the movie theater projector, had saved for him. As Larsen observes, in both churches and movie theaters we “set aside our time and our space to gather in community and join our concentration … to apply our intellectual, emotional, and artistic prowess toward considering the world and our purpose within it.”

At the time I worked at the Drafthouse I was in college at Catholic University, having just graduated from the Jesuit high school Georgetown Prep. I explain all this because the world of church and Saint Ignatius and the flickering nighttime realm of the theater were both holy expressions to me. The magical world of movies where I lived every night seems beyond the propaganda aims of the left, which wanted to use film for social change, and the blinkered ideology of the right, which praises junk like Death Wish and crosses out entire genres of film as unworthy of analysis.

All these years later Larsen explains exactly what I felt at the time (and still do today):

Among the Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius, founder of the Jesuits, is an understanding of praise that involves the whole scope of creation. “Man was created to praise, reverence, and serve God our Lord and in this way to save his soul,” Ignatius wrote. “The other things on Earth are created to for man’s use, to help him reach the end for which he was created. Surely some of those “other things” can be movement, light, colors, sound—the building blocks of cinema (and the main characters of Genesis 1).

This is why prayers of praise are delightful. They can be endlessly creative. We do not worship a cruel God who demands quotas of praise in rigidly prescribed formats, as if he is the anal-retentive king and we are his sycophantic couriers. He wants our praise to be creative, to involve the full richness of the Earth (the Pandora he has made), and to reflect our own ingenuity as created beings. And so the Bible models many forms of playful praise, from the lute and harp of the Psalms to the Isaiah-influenced doxologies of the apostle Paul. Likewise, our different church traditions evoke praise in a host of ways.… On occasion, [prayerful praise] speaks the language of cinema.

To which, I think, George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Mel Gibson would say, amen.

Mark Judge is a writer and filmmaker in Washington, D.C.