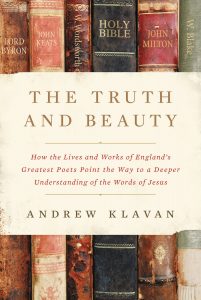

By Andrew Klavan.

Zondervan Books, 2022.

Hardcover, 272 pages, $26.99.

Reviewed by Emeline McClellan.

English prose has entered a new phase, as anyone who frequents the New York Times opinion page can testify. Gone are the long, twisty sentences of eighteenth-century polemicists, the flowery phrases of nineteenth-century moralists, and the clever barbs of twentieth-century reporters. Today’s sentences are bold and tactile, pulsating with verbs and nouns, packed with tastes and textures and colors. They speak about things: the material stuff of everyday experience.

That stylistic change mirrors a more fundamental philosophical shift away from scientism towards vague “spirituality.” After decades of lab-coat rule, many postmodern people are beginning to buck against materialistic explanations of the universe. Personal narratives, not scientific theories, are becoming the new truth. In this climate, it is no surprise to find twenty-first-century journalists telling stories. By weaving their experiences into narrative form, writers are hunting for the primary thing science cannot offer: the meaning behind material existence.

Few understand today’s search for meaning better than Andrew Klavan, an award-winning novelist, screenwriter, and cultural commentator with a penchant for the literary classics. His most recent work of nonfiction, The Truth and Beauty: How the Lives and Works of England’s Greatest Poets Point the Way to a Deeper Understanding of the Words of Jesus, addresses head-on why postmodern people, the supposedly hard bitten heirs of scientism, cannot stop molding material facts into narratives.

The Truth and Beauty belongs to a maverick genre of its own—half-story, half-philosophy, woven from history, literary analysis, and theology. Addressing Christians or would-be Christians, Klavan documents his own attempt to understand Jesus better, not as the mouthpiece of a creed, but as a Man. In reality, though, Klavan’s strength is not his theology—which, too often, drifts into verbal sogginess—but his uncanny knack for diagnosing many of postmodernity’s ills: our restlessness under scientism, our contempt for femininity, and, as he makes clear, our resistance to the one Person who gives life meaning.

That resistance is not new, Klavan argues. Back in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Romantic poets such as Wordsworth and Coleridge were grappling with similarly relativistic, materialistic, and radical contemporaries. By the early 1800s, Enlightenment thinkers had rejected Christianity in favor of reason and science, Newton’s laws had replaced divine providence, and the French Revolution had left its followers disillusioned, with little reason to trust radical utopians any more than they trusted the Bible—and no answer to Pilate’s querulous dismissal of truth.

Klavan’s chapter on Hamlet—where his prose takes a murky, creepy turn—presents the epistemological challenge to scientific materialism: “Without some sort of [metaphysical] standard of perception…there can be no truth at all that goes unquestioned, no truth we hold self-evident, no axioms of morality, no way to determine what is objectively right and wrong.” Science, in other words, cannot tell us whether to trust our reason and perceptions. In the materialistic nineteenth century, unbelief naturally became “the central principle of the age,” and a cadre of cynics succeeded in “disenchant[ing] the human territory.”

In response, the Romantics aimed to re-enchant life by proving that Newton’s material universe retained spiritual significance. Their poetry suggested a radically conservative idea: Human perception—including imagination, emotion, and story-telling—captures the world as it really is. God created the universe to be beautiful when perceived through our eyes. “When you see the rain fall,” Klavan summarizes, “it’s not the rain God sees, not the rain as it is, not the fundamental rain. It’s the rain man sees: the falling silver rain. But it’s true rain, nonetheless. It wets the fields. It makes the crops grow. Your internal experience is a human version of outer reality.” Beauty is not a trick of human perception, foisted onto meaningless combinations of atoms. The beauty we see is truth, because God put it there for us to see.

Klavan’s equation of truth and beauty may sound unfamiliar to postmoderns. His viewpoint implies, first, that beauty is just as real and verifiable as truth, and, second, that we can know something of objective truth by knowing beauty—and not just the beauty of art.

Klavan’s most unique and moving chapter, an analysis of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, argues that the beauty of femininity stands as the final bulwark of truth against scientism and materialism. Woman, he argues, represents the fundamental meaningfulness of God’s creation. First, and most obviously, her body exists to create living beings from mere matter—that is, to generate babies. By producing physical creatures with metaphysical value, she imitates God’s act of creation. Second, and just as crucially, a woman nurtures her child’s developing notion of himself, God, and the world—and, ultimately, his sense that the universe has meaning. She serves as “the conduit for the spiritual life of mankind.” Woman creates life and beauty from matter, just like the poets, and, through motherhood, she creates the poets, too.

Embracing traditional femininity thus means acknowledging that the physical world has meaning. A culture that embraces, as he puts it, the “mom-sage-creator-businesswoman-homemaker of Proverbs 31” cannot sustain scientific materialism, which denies any transcendent significance behind matter.

As a result, materialism and feminism emerged together. Once factories, machines, and appliances had begun stripping women of their traditional home-making tasks, Mary Shelley’s culture started agitating for “free love,” which divided sex from marriage and family, subjected women to men’s desires, and ushered in the age of planned parenthood. Today, women are no longer the conduit of spiritual life. Our materialism can proceed unchecked, Klavan concludes, as long as we keep denying “the inconvenient fertility of the female body and the humanity-producing power of motherly love.” His observations in this chapter deserve an entire book on their own.

For two-thirds of The Truth and Beauty, Klavan does exactly what he says artists should do: he perceives what things mean and beautifully speaks that meaning. With a novelist’s scintillating touch, he extracts significance from works as disparate as Hamlet, Paradise Lost, Frankenstein, Rime of the Ancient Mariner, and Ode to a Grecian Urn. These pages demand to be devoured in one sitting.

Disappointingly, however, his final chapter, “A Romantic Meditation on the Gospels,” misses the mark. Klavan’s overall conclusion is true: “Our lives are meant to express the truth and beauty which is woven into the fabric of God’s creation.” Obedience to God transforms our bodies, actions, and artistic creations into what Klavan calls “the language of the Logos”—a fuzzy formulation signifying something along the lines of “what God intends humans to be.”

In many places, this kind of imprecise language takes Klavan outside Christian orthodoxy. He claims, for instance, that “in the Trinity, the object we are trying to describe is God the Father, the term we use to describe it is Jesus the Son, and when we grasp that idea, we are filled with the Spirit”—a formula far too bold for good Trinitarian theology.

Even when technically orthodox, Klavan tends to muddle his language. He says, for instance, that Christ “really rose from the dead, and, rising…showed that the Word speaks the body into existence and that if the body speaks the Word, it becomes part of its endless creation and will be spoken into life without end.” It is difficult to explain what this sentence means, or how it improves upon the plain biblical statement that Christ offers life in abundance.

Linguistic slush like this will not trouble unbelievers. But for Christians, it is important that someone claiming to articulate a Christian perspective on art and language take more care over his own verbiage.

This section, however, contains many gems of insight. Klavan argues that “God is always male to us because we are always female to him, the bride to his bridegroom”—something liberal theologians emphatically reject. Later, in another slight to theological liberals, Klavan reminds us that “Jesus never says his injunctions will make the world a better place.” Rather, Christ wants us to change the world by “chang[ing] ourselves to be more in accordance with him.” Here, Klavan uses clear language to express the Bible’s plain meaning.

Theological fuzziness aside, The Truth and Beauty remains, for the most part, both true and beautiful. By upholding the Gospels, Klavan offers just the right prescription to postmoderns emerging from scientific materialism—and eager to be told what their stories mean.

Emeline McClellan graduated with an M.Phil. in Classics from Cambridge University. She works in Washington, D.C.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!