By Kate Cooper.

Basic Books, 2023.

Hardcover, 304 pages, $30.

Reviewed by Paul Krause.

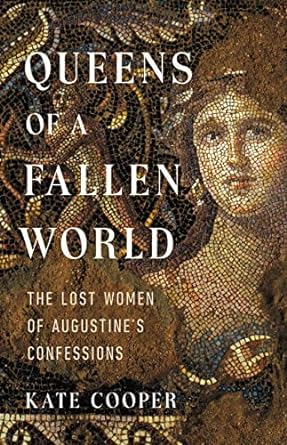

Saint Augustine was a momma’s boy. He was also smitten by the beauty and charm of women, from the concubine with whom he had a son to Virgil’s poetic representation of Queen Dido whom he wept for in her desolation instead of weeping for the desolation of his own soul. The tears, echoes, and shadows of women pervade the pages of Augustine’s Confessions and in a brilliant new book, Queens of a Fallen World, Kate Cooper brings them to life in an age rife with tumultuous controversy and conflict.

“Augustine was a man who noticed women,” Cooper writes of the bishop of Hippo. That may be one of the greatest understatements when describing Augustine. While Augustine noticed women, he also “[doesn’t] expect women to be silent. He often found them memorable, precisely for what they said.” To this extent we should be very thankful that Augustine preserved their voices, even if he ultimately speaks for them in the Confessions. Because of Augustine’s preservation of their memory and voices in his famous work, Cooper places various women at the center of the controversies that shaped the life and thought of the great saint and thereby frees them from Augustine’s unintentional imprisonment from his own narrative.

We all know Saint Monica (“Monnica” in Cooper’s book), Augustine’s complex, imperfect, but devoted mother. Some of us may also know Justina, the empress caught between two worlds colliding against her own—the world of an ascendant Nicene Christianity and the eastern Roman Empire breathing over the west while the sun above the western half of the empire began setting under the plagues of civil war, usurpation, and barbarian invasion. Two other women are referenced by Augustine though they do not have names: “Tacita” (the young girl with whom Augustine was arranged to be married when in Milan) and “Una” (the unnamed concubine whom Augustine says was the “only woman he ever loved”). These placeholder names, given to us by scholars for their humanization, mean “the silent one” and “the one” respectively.

We all also know Augustine, the great saint and bishop of Hippo who was the most influential theologian and philosopher of Western Christianity. He is generally remembered, somewhat inaccurately, as the inventor of the doctrine of original sin and, more accurately, as the man who forever changed the western understanding of human nature from the rational animal of Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics to creature of love where the human heart is the most important aspect of our existence. As Augustine famously says, “I was in love with the idea of love” and, “My weight is my love. Wherever I am carried, my love is carrying me.”

But where did Augustine really get his ideas “about love and marriage, about human disappointment and hope?” Cooper asks. Cooper convincingly argues that it was the women in Augustine’s life who taught him most about what he is most famous for, and thus “whether they knew it or not, the people in Augustine’s life—the women in his life—had a profound impact on the lives of Christians for centuries to come.” We who live today still stand in that shadow and culture which believes that “Love is God” (as Augustine wrote in his homilies on the epistles of John), and are also living in the shadow of the women who taught Augustine about love.

The Women in Augustine’s Life

Queens of a Fallen World is a very special history given the period in which it is set. The late fourth century and the early fifth century is generally remembered as part of the final one hundred years of the Roman Empire (in the west), beset by civil war, barbarian migration, and the eventual decline and fall of the imperial polity in the lands of central and western Europe. It is the world of generals and emperors, barbarian chieftains and warlords, the sack of Rome by Alaric, and the scourge of God: Atilla the Hun. This world of intense transformation is dominated by men; not just men of action on the fields of blood and war but also men of action writing about “the inner human being and the transcendent nature of the soul.” Thanks to Cooper, we now have a book that gives us this exciting and excruciating time from the perspective of the women who were ever present but often left at the margins of historical and literary memory.

In many ways, Cooper’s work is part biography and part cultural history when she reflects on the four women who dance across Augustine’s heart and soul and the pages of the Confessions. We meet the world of imperial politics through Justina, whom history has remembered as a heretic and persecutor of Christians. We encounter the social fabric and life of women under the heavy hand of the paterfamilias whose love lives were “arranged…as a way of strengthening the family’s position” when Cooper talks about “Tacita.” We journey into the breadbasket of the Roman Empire, North Africa, where old and new cultures met at the “crossroads of the Roman and Berber civilizations” with Monica who was the living embodiment of ancient multiculturalism. We also land into the thick of the complex web of human relations between male and female, slave and free, with Augustine’s soulmate “Una,” and how this imbalance and dynamic of human relations paved the highway for late antique views of love, lust, and power. All of this from the eyes of “the lost women of Augustine’s Confessions.”

The stories of Justina, Monica, Tacita, Una, and Augustine all come to a climax in Milan—the place of Augustine’s conversion but also the place of political rivalry with the looming invasion of Magnus Maximus and where all the women of the Confessions meet at the crossroad of agonizing separation.

Cooper’s brilliant reading of this moment corrects many of the popular misconceptions about Augustine. People still wrongly believe Augustine condemned sex as the highway to sin, a misconception promoted both by Christians and non-Christians. While scholars of Augustine have started to move away from this ascetic narrative ideology begotten by Possidius (Augustine’s first biographer), Cooper does such a great job looking closely at Augustine’s writings that we wonder how this misconception ever emerged in the first place. It was not sexual sin, per se, that caused Augustine’s grief as he left Una, broke off his arranged marriage with Tacita, and compelled him to take up vows of monkish chastity. It was the guilt of having abandoned Una that led him to see chastity as the only way to assuage his guilt and remain faithful to her as she promised to remain faithful to him.

Getting to Know Una

As Augustine said of Una in the Confessions, she was “the only woman I ever loved.” Augustine, even when writing the Confessions, could not get Una out of his mind. He was still haunted by both the felicity and the guilt of their relationship, not so much that they had an illicit relationship but more in how the relationship ended. Una looms in the background as Augustine preached on the virtues of chastity and virginity, as well as on the revolutionary shift he wrought to the world reflecting on newfound moral responsibilities men had to women which slowly eroded the tyranny of the male-dominated Roman jurisprudence on marriage.

Augustine’s preaching on love and marriage, chastity and virginity, was his way of honoring Una’s life, his way of trying to reconcile his still apparent love for her even though they were separated. Augustine’s writings can be understood as his agonizing love letters to Una even after parting. “The root of [Augustine’s] problem,” Cooper writes, “was not sexual desire. It was ambition.” The late-in-life Augustine broke sharply with the ascetic readings of Genesis 2-3; Adam and Eve did in fact have the gift of sex in the Garden of Eden before the Fall. What they did not have was the corrupting taint of pride and the self-centered ambition that flows from pride, the ambitious pride that ultimately ruined sex for Augustine. Cooper summarizes this often-forgotten part of Augustine’s sexual ethic and theology, “The original sin had nothing to do with sex: it was the sin of pride…The problem was that [Adam and Eve] had thought they might live independently of God who created them. Sex in Paradise, Augustine believed, would have been unimaginably exquisite.”

Augustine could never escape the haunting guilt of this disastrous separation with Una. Augustine’s mature theology of charity is that we learn the reality of our own souls of love in how we respond to others in distress and disaster, and this outlook from Augustine clearly recalls Una and his failure in treating her with the love she deserved as an image of Divine Love. Augustine wanted others to learn from his mistakes and his writings served as a form of personal atonement between the lines.

What Augustine Learned

Queens of a Fallen World is a superb book revealing the hidden, but upon closer inspection, not-so-hidden role that women had in shaping Augustine’s thinking. Cooper brings to life the women who are always lurking somewhere in Augustine’s voluminous writings. “Each of the women,” our sagacious author notes, “contributed to shaping Augustine’s world and his worldview, along with the legacy he left to history.”

From Monica Augustine learned the power of stories, even stories of failure, and how we can grow intellectually and spiritually from those stories. From Justina, though he takes Ambrose’s distortion of her, Augustine rejected the idea of the political unity of church and state—the church should ultimately remain independent of the state even if the two can, and oftentimes should, work together on common causes. From Una and Tacita, but most especially Una, Augustine developed a complex even if imperfect ethical framework of human relationships and how men and women should relate to each other.

Faithfulness, in whatever form it takes, should be the governing heart that guides men and women with one another. Faithfulness is the true heart of marriage too. I might go further to suggest that Augustine’s theology of faithfulness to God and God’s faithfulness to humanity was his way of trying to remain faithful to Una and thereby be absolved of the guilt he clearly felt in abandoning her. God will not abandon us, and, therefore, by being forever united with God Augustine could implicitly rest with some peace that he was still faithful to, and united with, Una.

Kate Cooper has given the world a most important book. The towering genius of Augustine was not his own. Women contributed to that genius. And even though we know the name of Monica, we should know the woman whom Augustine truly and genuinely loved and who probably influenced him more than any other. We can, and should, call her Una—perhaps even Saint Una.

Paul Krause is the editor-in-chief of VoegelinView and the author of Finding Arcadia: Wisdom, Truth, and Love in the Classics (Academica Press, 2023) and The Odyssey of Love: A Christian Guide to the Great Books (Wipf and Stock, 2021).

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!