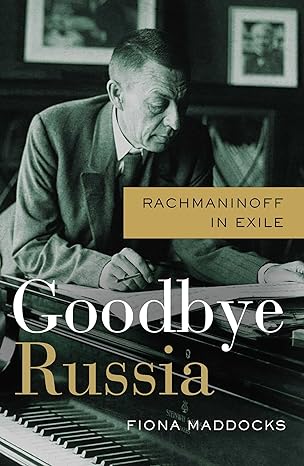

By Fiona Maddocks.

Pegasus Books, 2024.

Hardcover, 384 pages, $29.95.

Reviewed by Robert Bellafiore.

In the last years of Romanov Russia, Sergei Rachmaninoff was enjoying life as a musical giant, composing such titanic hits as the third piano concerto and second symphony, building his renown as one of the great pianists of the age, and savoring the luxuries of an Old Regime aristocrat. When that world collapsed amid the Bolshevik revolution, he had the relative fortune to flee, escaping to America to make a new life for himself in New York City.

The story of the musician’s second act in his new home, and of the enduring memories of the old home to which he would never return, is well told in Fiona Maddocks’s Goodbye Russia. Maddocks is an able guide as she wanders through the adventures, disappointments, and adjustments that Rachmaninoff would experience from his escape in 1917 to his death in 1943.

Rachmaninoff in Exile’s easy charm and nonchalance make for a contrast to the man himself, or at least to the man as many encountered him—his fellow Russian composer-in-exile Stravinsky called him a “six-and-a half-foot-tall scowl.” One might similarly call much of his own music, in honor of his huge hands, an “octave-and-a-half-wide scowl”: invariably noble, but also brooding and intimidating—especially for the pianist attempting to play it. It was with some justification, for instance, that one critic called his Prelude in C sharp minor, a work so often demanded at concerts that Rachmaninoff came to hate it, “that piece of portentous Siberian gloom.”

Maddocks does much to humanize Rachmaninoff, though, as she describes his adaptation to the New World, starting with a performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at his first concert after his arrival. Though in Russia he was equal parts composer and pianist, financial constraints in America forced him to become a full-time concert pianist, and he submitted himself to a strenuous concert circuit for the next few decades. But that didn’t stop him from finding time for a new, very American hobby: cars, which he told one interviewer were one of his favorite things about America, along with its egalitarian spirit and excellent orchestras.

The intimacy and idiosyncrasy of Goodbye Russia’s portrait is aided by generous quotations from relatives, colleagues, fans, and critics, and Maddocks often lets Rachmaninoff and others do the talking for her, sampling from letters and conversations. To borrow from the title of a 1945 film full of Rachmaninoff’s music, the book is full of “brief encounters” with an impressive cast, many of which reveal the pianist’s dry humor. When Mickey Mouse performed the C sharp minor Prelude in only his second film, Rachmaninoff told Walt Disney, “I have heard my inescapable piece done marvelously by some of the best pianists, and murdered cruelly by amateurs, but I was never more stirred than by the performance of Maestro Mouse.” He was also a fan of Charlie Chaplin and once had a hilarious, if predictably exasperating, interaction with Harpo Marx.

But the life of an exile is a hard one. Rachmaninoff struggled with an enduring sense of estrangement, both as a Russian in America, and as a musical conservative amid the tumult of modernism. He sought out the company of fellow Russian émigrés, among whom he could let his dour guard down; but to the outside world, he appeared, as the New Yorker put it, “austere, solitary, aristocratic, morosely sensitive and simple.”

Maddocks’s discussions of Rachmaninoff’s life and work raise a tricky question: to what extent do a composer’s works express something about his homeland? One might often detect “Russianness” in Rachmaninoff’s music, and with good reason, in the case of such works as his Three Russian Songs. But in other cases, perhaps we are only fooling ourselves. It’s easy, once we know that a piece of music is by a Russian, to see onion domes and borscht in the mind’s eye; but would we have done so if we hadn’t been prompted by our knowledge of his heritage? Rachmaninoff, at least, would have hoped so, insisting, “I am a Russian composer, and the land of my birth has influenced my temperament and outlook. My music is the product of my temperament, and so it is Russian music.”

A similar thorny relationship is that between an artist’s life and his work. It is so natural to hear joyful music and deduce that the composer was having a good day, or to hear sorrowful music and suspect a recent break-up. But as Maddocks reminds us, it’s not so simple. For example, the Symphonic Dances—Rachmaninoff’s last work—seem to exhibit a “mood of longing for Russia, for the past.” Surely the piece is a “wrapping up of his creative output,” a dying expat’s final cry for the motherland? Perhaps, but older works, such as his second piano concerto, written decades earlier in his homeland, have that same “Russian melancholy,” so reading too much into one or the other work will be a risky venture. At the other end of his life, that C sharp minor Prelude, however much we might hear in it the dread of impending death, was written when he was a spry nineteen. Life is one thing, and art is another; but that doesn’t prevent Maddocks from offering insight into both.

Accompanying the great sense of place in Rachmaninoff’s music, as Maddocks shows, is the sense of time—specifically, the past. Even as his fellow Russians Stravinsky and Prokofiev charged ahead with the cerebral sounds of the modern age, Rachmaninoff remained committed to an older Romantic idiom, full of melody and emotion. Sticking in his recitals to old warhorses such as Bach, Beethoven, and Schubert, he had no interest in the new music that every day made him more of a relic. Indeed, the book’s subtitle, Rachmaninoff in Exile, could apply equally well to his musical life. Refusing to change with the times, he settled instead for reigning as, in the words of one critic, “One of the musical monarchs of an age almost past.” And he recognized himself as such, calling himself a “ghost wandering in a world made alien. … I cannot cast out my musical gods in a moment and bend the knee to new ones.”

We in the audience, at least, can appreciate his commitment to, as he put it, the “divine rules, the rules of harmony,” and his insistence that those rules would bear fruit just as they always had. Forced as he was to pay the bills through his recitals, he had to put his composing on a near-total halt, producing only six new compositions in exile. But they are among his best and most beloved, especially the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini.

Here, especially, knowing the history shapes the listening: realizing that these are Rachmaninoff’s exile works, rare breaks in a decades-long compositional silence, sends a further wave of Russian melancholy upon this listener. One cannot hear them, knowing what they are, without thinking of all the music we will never hear—those works which Rachmaninoff might have written had his old world survived. But it is a melancholy that, if it makes us long for unknowable harmonies, also reminds us to savor all the more the music he did give us. For that, and for helping us to appreciate them, both Rachmaninoff and Maddocks deserve our thanks.

Robert Bellafiore is Research Manager at the Foundation for American Innovation.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!