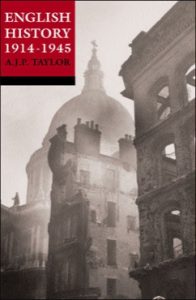

The Book that Shaped the Study of England Between the Wars

The Oxford History of England, Volume XV.

by A. J. P. Taylor.

Oxford University Press, 1965.

By John Rossi

Alan John Percivale Taylor (1906–1990) was the “bad boy” of the English historical profession. He was a controversialist with his strong revisionist interpretations of British and European diplomatic history. His Origins of the Second World War (1961) argued that World War II was an accident for which the Allies shared responsibility and that Hitler had no long-range plans, that rather he was an improviser and in most ways was a rational statesman little different from Bismarck.

Taylor seemed an unlikely choice to write the final volume in the highly regarded Oxford History of England series on England between the outbreak of World War I and the end of World War II. And yet he produced what is regarded as the best single volume on the topic as well as the best-selling volume in the series. The series editor, the highly regarded scholar of Late Stuart England, Sir George Clarke, knew what he was doing and took a chance on the controversial Taylor. He wanted a readable history of one of the most important periods in modern British history and got more than he asked for.

When Taylor began to write there were already several general histories of England in the twentieth century including a pioneering one by Charles Loch Mowat, Britain Between the Wars (1955). Taylor admired Mowat’s analysis of the period, admitting that he found himself tempted to follow Mowat’s interpretation of events.

There is no overarching thesis to Taylor’s examination of the thirty-plus years covered. In many ways he is an old-fashioned chronicler, telling a story that is gripping, inspiring, and tragic at the same time—British deaths in the two world wars were over 1.1 million in a country with a population a little over 40 million. Taylor believed history speaks for itself and he celebrated that, despite all that befell England during these years, she “had risen all the same.”

Taylor’s history begins, as he writes, “on the day, 4 August 1914, almost at the hour, 11 p.m., when the volume by Sir Robert Ensor in this history [in the series] ends.” World War I, he argues, transformed England. It destroyed the Liberal party and the issues that it believed in (free trade, Home Rule for Ireland, laissez faire economics), saw the rise of the Labour Party as the voice of the left, and witnessed the passing of English financial dominance to the United States. Taylor laments few of these changes, believing that for the first time the war gave the nation “the most democratic push in England’s history,” including first-time voting rights for women, albeit at age thirty.

Part of this democratization he attributes to the emergence of the popular press as the voice of the people, a role he attributes largely to Lord Northcliffe and his invention of a newspaper for the masses, the Daily Mail. He agrees with Lloyd George’s observation that during the war, the popular press “performed the function which should have been performed by Parliament.”

World War I also produced one of Taylor’s heroes: David Lloyd George, who became Prime Minister in December 1916 and transformed the war into something close to a people’s struggle. (Taylor has a weakness for history’s bounders and Lloyd George, whose secretary was his mistress and who amassed a huge sum of money by selling peerages, was certainly a bounder of the first order.) Lloyd George fascinated Taylor as a master improviser, someone not bound by the rules of the past, and the man who by throwing away the book helped win the war for England. As Minister of Munitions Lloyd George was responsible for ending the shortage of shells that plagued England in the early years of the war. An example of his approach, as Taylor notes, is how he dealt with the need for the machine gun that changed the nature of warfare. The army said two machine guns per battalion were sufficient. Lloyd George suspected they were wrong and countered: take the Army’s figure. “Square it. Multiply by two. Then double again for good luck.” England ended the war with 240,000 machine guns.

Taylor had a low opinion of Herbert Asquith, who was PM when the war broke out, seeing him as hidebound, unimaginative, and worn out by the kind of political world the war created. He spent his weekends playing bridge and writing letters full of Cabinet secrets to a young girl who fascinated him. Taylor notes that Asquith was the first Prime Minister since the Younger Pitt to be “the worse for drink” on the front bench.

Little touches like this are scattered throughout the book. His footnotes and biographical sketches are not to be missed: George V wore his trousers “creased at the sides, not front and back.” John Maynard Keynes “invented modern economics.” The war brought the f-word into popular usage. Charlie Chaplin was “England’s gift to the world … as timeless as Shakespeare and as great.”

Taylor devotes about half the middle portion of the book to the problems that England confronted in the two decades after the war: chronic unemployment, the decline of major industries especially coal mining, shipbuilding, and textiles. He points out that while England recovered by the mid-1920s from many of the war’s scars, it failed to create new industries as the United States did during that decade. As in the first part of the book he has his favorites, including the much-maligned Ramsay MacDonald, who many on the left believed betrayed the Labour party by forming a National government with the Conservatives during the economic crisis caused by the Depression. He admires the fact that MacDonald refused to betray his pacifist principles and support the war, a stance that kept him out of power for almost a decade.

Taylor has kind words for King George V, who reigned through the first twenty-plus years covered in the book, arguing that he was the last monarch to make a significant political contribution. He counseled compromise in dealing with the Irish revolt and recommended giving the Labour party a fair chance when it formed its first government. He also was a moderating force during the General Strike when some Conservative hotheads, including Winston Churchill, sought a showdown with the unions.

Taylor has a low opinion of the two men who dominated English politics between the wars: Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain. Taylor believed that Baldwin was a master politician who “in his lazy fashion truly represented” the two decades after World War I. He let serious issues such as unemployment and rearmament drift. Taylor does give him credit for handling the abdication of Edward VIII, who Taylor regards as little more than a playboy out of touch with English people, unlike his father.

Taylor’s treatment of World War II is less sure than his handling of the First World War. Partly this is a bibliographical problem. Some of the most important books on controversial aspects of World War II hadn’t appeared when Taylor wrote in the early 1960s. For example, Taylor wasn’t aware of the existence of Ultra, which gave the Allies access to German actions and helped shape the course of the war.

Taylor finds it difficult to like the aloof Chamberlain, whom he describes as “blinkered, narrow, impatient of criticism,” but admits that he was the most important figure in English politics from the mid-twenties until the outbreak of World War II. Despite what is commonly believed, he credits him with launching the rearmament of England in the 1930s. While criticizing Chamberlain for giving in to Hitler’s demands at the Munich Conference, Taylor notes that one can justify his actions by looking at the maturing of plans for British armaments in the eleven months of peace that followed: aircraft production increased from 240 to 660 a month during that time. Radar in October 1938 at the time of Munich just covered the Thames estuary. Eleven months later it covered the entire eastern coast.

Britain entered the war, according to Taylor, “blindly cheerful” but ill-prepared, believing that Germany would be strangled economically as had happened toward the end of World War I. They were surprised by the ease with which Germany absorbed the economic shock of the war and were further caught off guard by the ease with which she overran Western Europe in the spring of 1940.

Taylor doesn’t believe Hitler was serious about invading England, a view shared by most historians of the conflict. The victory in the battle of Britain he attributes to Air Marshal Hugh Dowding, who had to defy Churchill and the Cabinet to keep fighter wastage under control. For this, as Taylor notes in passing, he was relieved of command.

Taylor takes a dim view of the Allied bombing campaign, approving the conclusions of the official Bombing Survey that “bombing was very far from inflicting any crippling or decisive loss on the enemy …” He laments the loss for both sides in the bombing campaigns: 560,000 Germans and 60,000 British, to little purpose in his view.

Sprinkled throughout the discussion of the war are some Taylor touches. He has a low opinion of the Atlantic Charter and points out that the British interest in flank attacks in North Africa, Italy, and the Mediterranean was a way of keeping casualty figures low. He notes that, unlike the First World War, the Second didn’t produce what he describes as a distinctive British literature, a view readers of Waugh’s Sword of Honor might dispute. He may be right that the war didn’t produce the kind of poetry that the trench slaughter of World War I did.

Some of his footnotes are examples of Taylor’s provoking the reader. In discussing Hitler’s declaration of war against the United States after Pearl Harbor, he correctly notes that Germany wasn’t obligated by treaty to do so. Then he adds one of the paradoxes he loved so much. What, he asks, if Hitler, “raising the cry of the Yellow Peril, had declared war on America’s side.”

As throughout the other sections of the book Taylor selects his heroes carefully: Dowding and his role in the winning the Battle of Britain; the King and Queen for refusing to send their children abroad and for staying in London during the bombing. Ernest Bevin and Clement Attlee he lauds for proving that Labour was competent to help run the country. But of course, the real hero of the war was Churchill. In fact, Taylor’s history of the war is often a running commentary on what Churchill thought and did.

Churchill, Taylor argues, personified the mood of the nation at war. “He was an eccentric, which exactly suited the mood of the British people … [who] welcomed his romantic utterances” and utter contempt for Hitler. But he was not interested in fighting “an ideological war against ‘fascism’” but rather waging a nationalist conflict, one that would see the resumption of the old-fashioned balance of power that restrained German power in Europe. As late as 1943, for example, Churchill was willing to cut a deal with Mussolini, and even said kind words about Franco in Parliament, things anathema to the Americans and many in England.

Churchill, according to Taylor, knew that time was running out for a major British role in the war and so he tried to carefully husband British forces and lives as the war became increasingly an American- and Russian-dominated conflict. Taylor sums up Churchill’s contribution to Britain’s victory in the war with one of his typical aphorisms: “the saviour of his country.”

What, Taylor asks, was the effect of the war on Britain? “Imperial greatness was on the way out; the welfare state was on the way in. The British empire declined; the condition of the people improved. Few now … sang ‘England Arise.’ England had risen all the same.” Taylor believed that the war produced a revolution in English life and created a “nation more fully socialized than anything achieved by the conscious planning of Soviet Russia.”

Despite the numerous histories of England that have been written in the six decades since Taylor’s, his has not been surpassed, for all its idiosyncrasies, as the best single study of the period.

John Rossi is Professor Emeritus of History at La Salle University in Philadelphia.

Support The University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!