By Ben Peterson

At least since Sophocles’ dramatic telling of the bitter conflict between Antigone and Creon over the burial of Antigone’s traitorous brother, the tension between higher law and the benefits of a public order that promotes law abidingness has been present in Western political thought and experience. The idea of a law above the state, with roots in the Hebraic, Stoic, and Christian traditions, is one of the great ideas in human history. Neither the state and its agents, nor its positive laws, are above the higher law, the law of God.

Yet the idea of higher law is destabilizing to public order because the former claims authority to distinguish between just and unjust laws within the state, and the individual conscience often discerns the difference. In our day, the tension between higher law and general respect for public order emerges in the politics of race, characterized by protests, riots, calls for root-and-branch reform, and reactive appeals to law and order. With regard to these matters, we face perennial questions of political legitimacy and obligation. When, if ever, should one disobey a law? How should one pursue change in the case of social or legal injustice? Our discourse does not adequately address these questions, but two thoughtful people did in the 1960s, an era similarly marked by civil disobedience and unrest: civil rights activist Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. and public philosopher Charles Frankel. The attention to both higher law and public order these thinkers maintain are badly needed today.

Just and Unjust Laws

King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” provides a defense of the nonviolent, direct action strategy he adopted in his civil rights activism. In addition to King’s eloquent portrayal of injustice and stinging indictment of the “white moderate,” his letter addresses the justification for civil disobedience. The full series of letters, including two from a group of eight Christian and Jewish clergymen and King’s response to the second, includes a debate on the nature of law and order. King’s defense of nonviolent direct action is grounded in the Christian natural law tradition, and his demanding theory of civil disobedience gives attention to both the substantive justice of laws and the value of law and order. In a New York Times essay “Is it Right to Break the Law?” Frankel argues civil disobedience can be justified even in a democracy, but he also suggests a sense of gravity and moral constraint should attend such action.

King’s open letter, published on April 16, 1963, defends demonstrations in Birmingham against continued segregation and other injustices against black men and women that, while nonviolent, violated civil law and a court order, resulting in King’s arrest and confinement. King’s movement was successful in attracting media attention and ultimately support for civil rights legislation. Unlike the mayor of Albany, Georgia, Laurie Pritchett, who understood the strategy of nonviolent resistance and avoided excessive force, Birmingham Commissioner of Public Safety Eugene “Bull” Connor played into King’s hands by brutalizing protestors and attracting national media attention, as James Patterson notes in a chapter in Race and Covenant (2019).

“The city’s white power structure,” King argues, has “left the Negro community no alternative” to demonstrations designed to produce “tension” and force negotiations. Demonstrations are the last step in the process of civil disobedience, following “collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self purification; and direct action.” He advocates not “evading or defying the law” but willful acceptance of the penalty for disobeying an unjust law: “I submit that an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law.”

King’s reference to the “rabid segregationist” is noteworthy. In their April 12 letter describing King’s demonstrations as “unwise and untimely” and “strongly [urging] our own Negro community to withdraw support from these demonstrations, and to unite locally in working peacefully for a better Birmingham,” the clergymen refer to yet an earlier letter from January 16, an “appeal for law and order and common sense.” Notably, that letter is aimed at opponents of desegregation, written in anticipation of court decisions to desegregate schools and colleges in Alabama. There, the clergymen assert, “defiance is neither the right answer nor the solution,” perhaps responding to Alabama Gov. George Wallace’s inaugural address two days earlier declaring “segregation now, segregation tomorrow and segregation forever.” Opponents of desegregation, the feelings and concerns of which the clergymen acknowledge as sincere, should “pursue their convictions in the courts, and in the meantime peacefully… abide by the decisions of those same courts.”

A consistent thread runs through these clergymen’s messages to desegregation opponents and to King, whom they urge in the April letter to abandon the strategy of demonstrations and allow local black and white leadership to negotiate about racial issues: “We appeal to both our white and Negro citizenry to observe the principles of law and order and common sense.” A plausible reconstruction of the clergymen’s argument to King runs as follows: We urged whites to respect law and order and follow court rulings requiring desegregation, even though some find these rulings adverse to their interests and preferences. Blacks seeking change should likewise respect law and order.

King recognizes the concern as legitimate:

You express a great deal of anxiety over our willingness to break laws. This is certainly a legitimate concern. Since we so diligently urge people to obey the Supreme Court’s decision of 1954 outlawing segregation in the public schools, at first glance it may seem rather paradoxical for us to consciously break laws. One may well ask: “How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?” The answer lies in the fact that there are two types of laws: just and unjust. I would be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that “an unjust law is no law at all.”

King goes on to cite Thomas Aquinas, who defined law as “nothing but a certain ordinance of reason for the common good, made and promulgated by him who has care of the community.” A law not genuinely “of reason for the common good,” not “rooted in eternal law and natural law,” per King’s paraphrasing, is not a law.

King supports obedience to law, but only true law. How are we to know which laws are just and which unjust? How can we tell, for instance, that segregation does not reflect the natural order, as some of its defenders claimed? According to King, “Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust.” Segregation distorts human personality, erecting a superior-inferior relationship between white and black people where none exists. King’s argument rests on a truth claim about equal human worth, a claim the clergymen in fact express in the first of their letters: “That every human being is created in the image of God and is entitled to respect as a fellow human being with all basic rights, privileges, and responsibilities which belong to humanity.” Pope John Paul II argues on similar grounds in Evangelium vitae that civil laws, even if promulgated in a procedurally just manner, do not bind the conscience if they violate the moral law.

Critically, the conscientious objector submits to civil authority. King appeals to the example of the Christian martyrs and Socrates who, even as they defied public authority in the name of a higher law, submitted to death. The thrust of King’s argument is to set a high bar for civil disobedience and high standards for its conduct, and to defend a robust conception of law and order: “I had hoped that the white moderate would understand that law and order exist for the purpose of establishing justice and that when they fail in this purpose they become the dangerously structured dams that block the flow of social progress.” King appeals to a law transcending procedural propriety to justify nonviolent disobedience of unjust laws, while still respecting civil authority.

The “Grave Enterprise” of Civil Disobedience

Frankel, evaluating King’s activism, offers a similarly nuanced account of civil disobedience. Ruling out a position that civil disobedience is never justified in a democracy because of the possibility of participation in legislation, he nevertheless gives attention to “another side to the story”:

We may admire a man like Martin Luther King, who is prepared to defy the authorities in the name of a principle, and we may think that he is entirely in the right; just the same, his right to break the law cannot be officially recognized. No society, whether free or tyrannical, can give its citizens the right to break its laws: To ask it to do so is to ask it to proclaim, as a matter of law, that its laws are not laws.

In short, if anybody ever has a right to break the law, this cannot be a legal right under the law. It has to be a moral right against the law. And this moral right is not an unlimited right to disobey any law which one regards as unjust. It is a right that is hedged about, it seems to me, with important restrictions.

Since the justification for civil disobedience rests on a higher

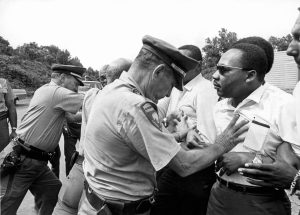

Dr. Martin Luther King being shoved back by Mississippi patrolmen during the 220 mile ‘March Against Fear’ from Memphis, Tennessee to Jackson, Mississippi, Mississippi, June 8, 1966. (Photo by Underwood Archives/Getty Images)

law of justice, such disobedience must also be constrained by that same law. Civil disobedience, he argues, is a “grave enterprise” and should only be undertaken in cases where basic moral principles are at stake and no legal path to reform is evident. In other words, Creon has a point as well as Antigone.

Riots and the Politics of Law and Order

Several waves of urban riots occurred in the second half of the 1960s, beginning with the Watts Riots in August 1965. Riots have since become a recurring feature of the politics of race in America. As Michael Framm writes in Law and Order (2005), Republican politicians including Barry Goldwater, Richard Nixon, and Ronald Reagan decried the use of civil disobedience as contributing to an atmosphere of disrespect for public authority, crafting a law and order message that resonated particularly with white people. They traced the disorder and rioting to a general lack of respect for law and order that proponents of civil disobedience encouraged by suggesting citizens may choose which laws to follow and which to disregard. Though perhaps overhyped for political gain, this is not an inappropriate concern. King himself acknowledged it with regard to the rabid segregationist, and Frankel counts the possibility of promoting disregard for law and the potential to inadvertently promote violence as among the factors a civilly disobedient activist must consider.

About a year before his assassination, which precipitated another series of riots, King addressed the riots of the “long hot summer of 1967” in an April 1967 speech at Stanford University entitled “The Other America.” The oft quoted line, that “in the final analysis, a riot is the language of the unheard,” comes after King’s reiteration of his stance that “riots are socially destructive and self-defeating” and “nonviolence is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom and justice.” King condemns riots and violence, even as he urges attention to the systemic conditions

ostensibly generating them. Some research supports the plausibility of King’s claims that economic and social deprivation contributes to rioting and that “violent protests” or riots are not as effective politically as nonviolent civil disobedience.

The great tension between higher law and public order, between Antigone and Creon, persists unresolved. From both a strategic and a moral perspective, attention to higher law and social reform needs to be balanced with respect for civil authority and public order.

Ben Peterson is an assistant professor of political science at Abilene Christian University. You can follow him on twitter @ben_2_long.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!