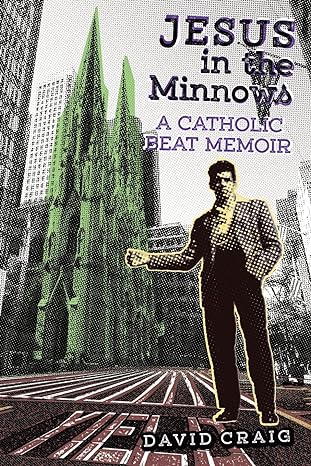

By David Craig.

Angelico Press, 2023.

Paperback, 216 pages, $17.95.

Reviewed by Alex Taylor.

There are two types of people in the world. Those who like the Beat poets and those…well. Beat poet turned monastic Thomas Merton and his Catholic aesthete editor Evelyn Waugh, who when editing Merton’s autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain for the English press cut about a third of the text. It’s not so much a question as to whether one admires the people esteemed by such as the so-called father of beatnik poetry Jack Kerouac, who wrote that “the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous Roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars,” but a question of whether that madness has found a measure within which to be expressed beautifully.

Retired Franciscan University creative writing professor David Craig has certainly had a mad, mad, mad, mad life, as documented in Jesus in the Minnows, a memoir published some 60 years after a movie with whose spirit it resonates. While his conversion provides tremendous fruit for contemplation, one wishes that he and some other Beats had displayed a bit more poetic temperance.

2022 was Kerouac’s centenary, and while he, like Merton, was Catholic (the former baptized young and the latter a convert), he is not generally remembered as such, but rather as the writer of On the Road (1957) and The Dharma Bums (1958), which while reflecting something of the author’s Catholic upbringing, spend more time revealing both a hedonistic life of heavy drinking and sex, and the author’s engagement with Buddhism. The result of the twenty days spent writing On the Road, fueled by caffeine, nicotine, and benzedrine, was necessarily uneven, mixing uninspired Hemingway-esque prose (think of The Sun Also Rises) with the occasional moment of transcendence which appears like a moment of light across the windshield during a dark drive through the countryside. David Craig, having a much greater remove from his tumultuous beatnik past, excels the so-called master of the movement: a full third of his memoir is especially worth reading, even if the beginning drags and the ending is somewhat less than satisfactory.

Jesus in the Minnows consists essentially of three parts, with two short epilogues. The first section documents Craig’s journey from southeastern Ohio, where he spent his years after graduating college working for the welfare system, to Cleveland, where he begins to discover a discontent with the casual hedonism of smoking marijuana, hooking up, and taking psilocybin mushrooms while in graduate school. His prose, while drifting too much into a Kerouackian stream-of-consciousness, does occasionally provide the reader with beautifully written paragraphs, and although the author generally eschews descriptions of obscenities, his characters might not be as conscientious. While St. Augustine in his Confessions recounted a similarly depraved delayed-adolescence, he was a bit more cautious in what details he chose to include for his flock. However, both Augustine and Craig reflect a keenly reflective conscience at times when they reflect on their past misdeeds. What slowly becomes evident is both that the future Church Father and the future creative writing professor were looking for sanctity. Craig writes, “I had never, in my whole life, now that I thought about it, met a person whom I finally admired. The more you got to know someone, the more clear their peculiar nexus of psychology became—until you just had to walk away, get as far away from them as possible.”

This revulsion from the concrete messiness of the human heart was to change, as Craig recounts in the second part, wherein he takes the odd step, after an encounter with some Catholic college girls, of traveling to Canada and staying awhile at the main center of the Madonna House apostolate in Combermere. There he finds men and women living in harmony, untroubled by the concupiscence which so characterizes his own gaze, and for the first time in the memoir recounts, hearing the women and men chant the Psalms in turn, being taken “somewhere else. To feeling—but not to me feeling.” The emotion felt in liturgy is unlike the egoistic pleasure brought on before with booze or such substances—and it feels to him like waking up in a new land. A new land where he continues to find souls who possess a peace that he learns to desire, such as a “very old woman named Yvonne” who had “an unhurried quality to her” despite “the trace of stress in her old facial lines” and the “holocaust number tattooed on her forearm.” But many of these figures are but foreshadowings of the portrait through speech given of the woman he calls Ekaterina (the foundress of Madonna House, Catherine Doherty), easily the most ecstatic moment in the memoir, in its exact middle, recalling Fr. Zosima in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, which Craig mentions having read at that time.

Ekaterina speaks to edify her brethren, reminding them that they ought to help the poor because they are the poor, and those who are truly poor are close to Christ himself, who dispossessed himself of the visible majesty of his Godhead to dwell among us in humble circumstances. In the middle of her testimony, she provides a story that shocks the community to silence, and one senses that this has been Craig’s model all along, even if he has not achieved it in the memoir as a whole. Ekaterina recalls a time when she stayed in Manhattan with Dorothy Day, who received a prostitute with hospitality, even into the bed she was to share with her Russian guest because there was no other. “‘Having been a nurse, I wondered if this was a good idea. The thought of disease, tb, venereal infection, crossed my mind. . . Dorothy realized my apprehension, looked at me calmly and said, ‘Ekaterina, this is the face of Christ.’” She certainly presented the face of Christ to Craig, who felt drawn to her, even as he knew she was not perfect, as none of us but Jesus and Mary are. Craig recounts parenthetically later that Ekaterina read his soul on one occasion, showing without words that she knew him as the “orphan and the lustful young man” both, a hard past which Christ would yet redeem.

The rest of the memoir’s middle section recounts Craig’s journey towards Easter, as he begins to develop a prayer life, and finally decides to undergo a Catholic charismatic ritual called the Baptism of the Holy Spirit. Craig’s experience being baptized in the spirit echoes that account written in Let the Fire Fall by the founder of the university at which he would one day teach, Fr. Michael Scanlan. Craig and Fr. Scanlan both describe, whether poetically or prosaically, a burning away of interior darkness, the rising tide of a fountain of life, a new sense of possibility. At the time of Fr. Scanlan’s experience, he was already a priest, his vocation sure but his mission still awaiting him. For Craig, however, his wayward travels to Denver and then to Texas then back to Fort Collins, Colorado, show a man whose Christianity had become certain, but whose path still lay shrouded in shadow. The second epilogue, something of a prose epithalamium (an ode written to a bride) for the woman who became his wife, is a fitting ending, but one wishes Craig had written of his turn to Steubenville and his time teaching there. While his conversion is manifest in this section of the narrative, one struggles to see his achievement of vocation, outside of a marriage whose privacy is veiled like the bride on her wedding day. Towards the memoir’s end, Craig mentions anticlimax, but also seems to provide one in his book.

Jesus in the Minnows places a firm coda on the Catholic beat phenomenon: firmly ensconcing what was good within it, while also reflectively revealing the unattractiveness of the hedonism from which the Lord led its members. This memoir will not be for everyone, but for those young people still enthralled by Kerouac or those of his generation who want to recall their own experience in the light of Christ, it will take them on quite the ride.

Alex Taylor is the Cowan Fellow for Criticism at the University of Dallas, where he teaches history, literature, and writing. He has written reviews, academic literary criticism, and poetry, both original lyrics and translations, for a variety of publications, and is currently at work on a dissertation on the problem of the modern city in the novels of Flannery O’Connor and Evelyn Waugh.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!