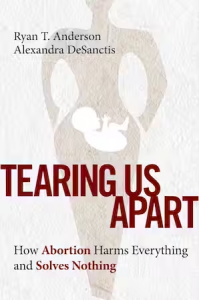

By Ryan T. Anderson and Alexandra DeSanctis.

Regnery Publishing, 2022.

Hardcover, 256 pages, $29.99.

Reviewed by Nicole M. King.

It is common practice for professors (or teaching assistants) of English composition classes to remove certain topics from the purview of their freshmen students’ argumentative essays. Some issues, goes the logic, have been hashed and rehashed so many times that the instructor would rather nail his own tongue to his desk than read another essay on the subject. Also, there are some issues on which one is unlikely to make any headway in a true argument. We have all picked our sides, and are unlikely to budge.

Abortion is often one such topic. It has been exhaustively researched and debated for decades. The usual pro-abortion strawman arguments and bad statistics are dragged out at every election cycle. And in the end, usually, nothing changes, because the demon called the sexual revolution requires abortion as its blood sacrifice to survive.

Into this milieu, Ryan Anderson and Alexandra DeSanctis dare to throw their two cents. The fundamental truth that Anderson and DeSanctis reiterate throughout the book is that abortion is evil because it destroys an innocent, helpless human life. A society that allows, supports, even encourages legal abortion is a society that is stained by bloodguilt. We are all harmed, the book’s subtitle says, because an evil this grave taints literally every aspect of communal human life.

The authors are right, of course. The problem is that when it comes to abortion, there is very little truly new to say. The best one can do is to comprehensively detail every aspect of the argument, but then, one must know to whom one is speaking. The question of the audience might be this book’s greatest weakness. The authors say that their audiences are pro-lifers and those on the fence who might not yet have made up their mind and need convincing that abortion is an evil that has damaged our country. But if pro-lifers are the intended audience and they have followed the debate reasonably well, they likely know much of this material already. Pro-abortion advocates will not be convinced, because the tone of the book is so overtly pro-life. If one considers oneself to be pro-life, but is going by a “gut feel” more than by facts, this book might be of considerable value.

Tearing Us Apart is divided into seven chapters, detailing the segments of humanity and society that abortion harms: the unborn child, women and the family, equality and choice, medicine, the rule of law, politics and the democratic process, and media and popular culture. There are times throughout the book where the authors display a bit of carelessness in their maligning of abortionists or the pro-choice movement. In the chapter titled “Abortion Harms Women and the Family,” for example, Anderson and DeSanctis cover the risks of chemical abortion. “Most significant,” they write, “women administer chemical abortions to themselves at home. If they require follow-up care for complications, it can be hard to come by. . . . . Sometimes, women don’t know what to expect or what side effects are normal, because abortionists decline to inform them of possible risks.” These statements require one to already have a dark view of abortionists. Why is follow-up care hard to come by? How often do abortionists really fail to inform patients of side effects, and why? The implication is that the abortion industry does not care that much for its patients—likely true, but again, if one’s goal is to convince someone on the fence, more facts and a less obviously bleak view of the abortion industry would be helpful.

The section on the abortion-breast cancer link similarly neglects to take the pro-abortion side seriously. The evidence is clear that the younger a woman is when she completes her first pregnancy, and especially if she then breastfeeds that child, the lower her risk of developing breast cancer. Why? When a girl reaches puberty, and later when she becomes pregnant, immature Type 1 and Type 2 tissue begin to grow in her breasts. These are the types of tissue most prone to cancer. Later pregnancy converts this tissue to Type 4 tissue, which is cancer resistant. So when a woman ends her pregnancy before the breasts have had a chance to finish their maturation to Type 4 tissue, she has increased her odds of cancer because she now has a greater amount of Type 1 and Type 2 tissue. These are some of the pro-life movement’s most valuable arguments, and the pro-choice movement knows it. This is why a simple Google search of “abortion and breast cancer” yields findings almost entirely on the pro-choice side. Anderson and DeSanctis do a service in drawing attention to this argument, yet they fail to adequately address the opposition, merely saying that abortion providers and the pro-choice movement “deny this connection, often promoting a single study that they argue disproves the abortion-breast cancer link.” There are lots of studies, and lots of arguments, and it would have been good to see more robust coverage of the opposition here.

In spite of such limitations, the book does a valuable service by summarizing some of the most powerful pro-life arguments. Perhaps the most powerful, and the least covered, are in the chapter “Abortion Harms Equality and Choice.” Worldwide, abortion kills more girls than boys, more ethnic minorities than Caucasians, and more disabled than non-disabled. In other words, abortion is the most socially acceptable form of sex discrimination, disability discrimination, and ethnic cleansing. Feminism and female equality are often touted as the reason for abortion. Yet, a true feminist has no choice but to recoil from a practice that is responsible for 90% of the gender imbalance in countries like India and China. Similarly, the authors cite a CBS news story reporting that Iceland was “leading the world” in the eradication of Down Syndrome. The horrifying truth is that Iceland kills all of its Down Syndrome babies in utero. The West’s simultaneous embrace of equality and abortion-on-demand is simply incompatible. You cannot be a feminist and support a practice that is used to eradicate girls. You cannot support the disabled and yet support a practice often used to kill them. And you cannot stand for racial equality and ignore the fact that the most vehement white supremacists (Richard Spencer, for example) say they need abortion to accomplish their mission.

Another powerful argument the authors use is that abortion “allows employers and society as a whole to treat the male body as the norm and female fertility as a problem to be solved—rather than a reality to structure social relations around.” No one has articulated this view more than the U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, who dispassionately told the Senate banking committee that overturning Roe “would have very damaging effects on the economy and would set women back decades.”

Where the authors truly shine is in the conclusion, where they detail some really creative policy solutions to promote a pro-life culture, including some recommendations for what to do after Roe and Casey have been overturned (this book was written before the Court did so). The authors recommend an incremental approach in the states that still codify Roe, including making sure that governments and employers alike are prevented from funding abortions. At a minimum, they advise eliminating government subsidization of abortion, strengthening conscience protections for health-care employees, and continuing to protect unborn children through existing legislation.

Weaknesses aside, the book is a valuable addition to the debate on abortion. Roe is gone, but the culture that created Roe—sexual license, feminism as the negation of female fertility, and a workplace that incentivizes sterility—is still prevalent. Overturning Roe was but the first step. Recreating a culture that values life at all stages is the war now to be won.

Nicole M. King is the Managing Editor of The Natural Family: An International Journal of Research and Policy.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!