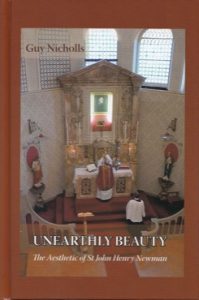

by Guy Nicholls.

Gracewing, 2019.

Hardcover, 352 pages, $36.

Reviewed by Daniel James Sundahl

It’s good to note at the beginning here that the Rev. Dr. Guy Nicholls is a priest at the Birmingham Oratory and directs the John Henry Newman Institute of Liturgical Music at Oscott College, the Birmingham Diocesan Seminary. There is serendipity in that since the Oratory was founded by St. John Henry Newman in 1849 as home for an English Catholic community, the Congregation of the Oratory of St. Philip Neri and whose salient characteristic was to conceal seriousness under great cheerfulness, simplicity, modesty, and humor. The Oratory houses the personal library of St. John Henry Newman.

Of course there is a vast corpus of writing on the life and thought of Newman, which means studies abound especially on Newman the theologian, all highly scholarly. The lacuna, however, is the absence of a compendium study of Newman’s aesthetics, the details of which can only be dredged from a wide-ranging survey of Newman the poet, the musician, novelist, and purveyor of other key elements of the arts, especially liturgy and church architecture. Father Nicholls’s thematic point is that Newman did not write any single work on beauty but the issue abounds with force and depth, albeit in complexity. Without suggesting that Newman’s aesthetic owed sources to Neo-Platonism, Nicholls considers Newman’s belief that beauty owns separate aspects, if not separate ideas. Newman does use the term “forms,” but believed that these “aspects” serve to bring us closer “to the transcendent truth of God through the sacramental signs embodied in His Church on earth.”

Following a fine introduction, Father Nicholls begins his commentary with a chapter on Newman’s poetical voice, subtitled the “Beauty of Holiness.” He adopts a metaphor to guide his commentary: “In Search of Eden.” The metaphor develops not only his understanding of Newman’s religious character but also how his understanding of beauty points to a reality beyond the experience and limits of our world of sense and perception—the otherworldliness of holy and heavenly beauty somehow hidden in this world.

And so it was that for Newman poetry surpasses prose writing because the poetical mind is home to the eternal forms of beauty and perfection. Newman did not want to be misunderstood as one interested in an aesthetic of beauty which neither leads to nothing beyond itself nor becomes a mere sort of self-advertising for the aesthetic self.

He finds this beauty in nature first because nature is alive and points beyond itself toward its Creator. Nature, in other words, is obviously alive and is not a “sullen” wall or an “eyeless tower” or a “tongueless” hall. Nature breathes, moves, and speaks, the effect of the “master-hand” hidden both behind and within. It’s the poet’s master-hand, then, which lets “rich nature … Unfold her varied plan.”

Much like his sermon voice, however, Newman suppressed the kind of poetry of, say, Wordsworthian dramatic self-advertisement, during which a spot of time leads him to utter that he again is strong; rather Newman is intending something beyond his personality and thus attempting to reach his auditors’ hearts. Near the end of his sermon “Wisdom and Innocence,” for example, he draws poetically upon the image of a garden at the close of day “when the shades lengthen, and the evening comes, and the busy world is hushed, and the fever for life is over and our work is done.”

The point is not abstract but clear that Newman held a lively hope in the brighter and more beautiful world of the eternal heaven which, as Father Nicholls writes, is “not merely a future reality, but … a present one awaiting its unveiling.” For Newman beauty is to be treated with caution and reverence rather than a mere “superficial sense of aesthetic pleasure.”

These are prisms, then, for Newman, who expands upon this unveiling in a longer poem in 1865, his majestic “The Dream of Gerontius,” a tour de force in which the main character nears death but then reawakens as a soul preparing for judgment. The prism of death and judgment draws the reader into a meditation on death and the afterlife, including what is phase seven in the poem when Gerontius begs to be taken up for purgatorial cleansing.

What is equally interesting is the poem’s music, its lyricism, which led to an Edward Elgar composition of the same name and arguing for the poem’s popularity in Newman’s own time.

“Echoes from our Home,” Music in Newman’s Life, is the third chapter in Father Nicholl’s survey of Newman’s aesthetic life. It’s a long biographical chapter beginning early in Newman’s life when at age ten he “began music.” When at Oxford, however, he discovered that music was looked down upon compared to intellectual pursuits. Newman persisted and played and attended concerts.

During Newman’s first tour abroad, and after long years of tutoring, he arrived at Rome in March 1833 and attended Vespers at St. Peters; he went to the Sistine Chapel on Maundy Thursday and Good Friday to hear Tenebrae sung by the papal choir. Father Nicholls makes the proper argument that Newman was “very struck” by the experience as very different from the Anglican order of music. It led Newman to make attempts to inquire into the history of Gregorian chant.

In March 1840 Newman moved from Oxford to Littlemore and, as Father Nicholls writes, we know that he tuned his violin and began to teach the children in singing. It was his ambition to teach the children a Gregorian chant, which he again noted they seemed to take to: “I see it makes them smile,” and “their voices are so thrilling as to make one sick with love.”

What Newman is searching for is some kind of aesthetic understanding of the affective power of liturgical music, its emotional intensity. But whence comes this extraordinary power?

Newman sensed a divine origin in music’s sounds, echoes from our true home. Father Nicholls quotes a small verse written by Newman which begins with a reference by Newman to Job 38:7: “Yes! For the morning stars together sang, / And angels joined the strains and heaven with Music sang / Upon this newly created world / Glory on glory shone throughout the whole, / And bliss on bliss was poured from pole to pole.”

Newman’s aesthetic development of music arises from his understanding of the music of the spheres, a harmonious force that is a rationally discernible unity underpinning the diversity of creation. From the basic material of merely seven or fourteen notes the consequence can be another metaphor for the outpouring of eternal harmony. Those notes, of course, are slender outfits for a sublimity and harmony that must of necessity be something much larger than a mere trick of art. Life, in other words, is always better with harmony even that harmony arising from nature.

Who, though, among composers, might be the great giver of rapturous compositions? Father Nicholls notes that, for Newman, Beethoven was the great bird singing, the gigantic nightingale, and he was unwilling to hear anything said against him.

When Newman founded the Oratory School, choral and instrumental music took place, much of it employed during worship and intending to lead kindly the heart with the voice full of praise and worship. For when we describe earthly music, Newman refers to its “attractive power from its sharing in the invisible, infinite glory of the Creator, whom [Newman] calls the ‘All-beautiful.’”

As Father Nicholls also makes clear, Newman never wrote a single treatise on beauty. However, his views become clear in Unearthly Beauty, which is both biography (showing different stages in Newman’s life) and an aesthetic analysis demonstrating that Newman’s developing perspective was teleological, beauty leading the heart toward a Catholic cultural worship of God in heaven.

Father Nicholls also shows the development of Newman’s own religious life from his Anglican years to his discovery and use of the Roman Breviary, which was applied to his aesthetic sense and which became in turn part of his doctrinal conviction. What is most interesting about Unearthly Beauty, then, is the emphasis on the continuity of Newman’s thought across different areas of his aesthetics, but always with the notion that beauty is rooted in the idea of God Himself. With the experience of beauty, Father Nicholls makes clear, Newman believed that we are granted an intimation of the heavenly harmony that is beyond the unaided intellect.

Thus it is understandable that apart from poetry, music, and liturgy, Newman would also turn his attention to church architecture with the same aesthetic in mind. One of his insights sheds light on many more, especially in relation to the Christian life and what is earthly pointing to what is unearthly. When Newman built the church at Littlemore, for example, he clarified or synthesized his years of pastoral work at the hamlet of Littlemore and the role of the Gothic in English Catholic church architecture, church furnishings, and decoration.

Father Nicholls makes it clear that Newman was not antagonistic to Gothic architecture, since Littlemore was built in the “plain Gothic style.” It was, however, “severely simple,” a “rectangular design … [with] lancet windows … filled with clear glass.” Littlemore became, then, the inspiration for several sermons by Newman on the symbolism of architecture and worship and represented Newman’s “developing appreciation of the symbolism between architecture in worship, suggesting as it did an analogy between architecture and heavenly glory.”

It was not, as Newman made clear, intended to be an example of Gothic revivalism, since Newman tended to associate Gothic with northern gloom. What he had in mind was the revised glory of English Gothic and the “most splendid building [he] ever saw”: St. Giles’ Catholic Church in Cheadle, designed by Augustus Pugin and said to have the most perfect church floor in all of Christendom.

Thus, as Father Nicholls again makes clear, for Newman, church architecture should lead to a building as a static statement, but should also stand as a home for a community and a context for the celebration of the liturgy. It should be gracious and winning, but always rooted in the idea of God Himself and the heavenly beauty of God rising from the sensory experience arising from church architecture.

Father Nicholls concludes Unearthly Beauty with a chapter titled “Entranced in the Vision of Truth and Sanctity.” He notes Newman’s belief that the material world is subordinate to the spiritual, which means the dependence of all beauty “perceived by the senses on the unseen, heavenly beauty of God.” The apprehension of heavenly beauty is of course that of divine perfection in the beatific vision of God. In that respect, Unearthly Beauty is a lovely companion to Bernard Dive’s John Henry Newman and the Imagination. Father Nicholls quotes Newman’s novel Callista when he notes that Newman “appeals in justification of the claim that we can, in fact, have an ‘imaginative apprehension’ and ‘real assent’ to God; namely the sense of moral obligation.”

Earthly beauty is, after all, a metaphor for the Unearthly Beauty found in the echo of a voice speaking to us, the friendly voice of God.

Daniel James Sundahl is Emeritus Professor in English and American Studies at Hillsdale College where he taught for thirty-three years.

Support The University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!