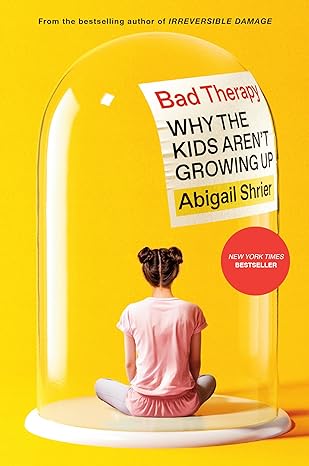

By Abigail Shrier.

Sentinel, 2024.

Hardcover, 320 pages, $30.

Reviewed by Robert Grant Price.

Abigail Shrier’s new book Bad Therapy has a simple thesis: children and teens get too much therapy and too much of that therapy is bad.

The book itself is not so simple. Shrier takes on the problem of distrust permeating daily life in North American households. Parents don’t trust themselves to help their troubled children, and the professionals called to care for the kids have violated the confidence they’ve been given. The result is stress and suspicion and an unprecedented mental health crisis among young people.

Bad Therapy, Shrier’s follow-up to Irreversible Damage, her blockbuster examination of the gender wars, gives the impression that institutions of education and healing should be treated as harmful unless proven otherwise. This isn’t an exaggerated reading of the book. All Shrier does—and does well—is to put into words, with ample sourcing, the feelings parents have been sharing with each other online and at the morning bus stop. The kids aren’t growing up. They’re a mess. And so are the therapists.

The book proceeds in three parts. In the first part, Shrier examines iatrogenesis—literally “originating with the healer”—and shows how the very act of therapy risks harming patients.

On the surface, this may seem counterintuitive when it comes to therapy. How can talking about your problems with a therapist be a problem? The answer Shrier offers is more logical than hysterical. Most people understand the risks associated with surgery, and so most people avoid unnecessary surgery whenever they can. Why risk infection, complications, and death if it can be avoided?

It’s the same with therapy. Lancing a psychological boil can cause all sorts of trouble. As Shrier details, therapy that encourages teenagers to focus excessively on themselves and their problems turns some of them into narcissistic hypochondriacs. This is the group of kids Shrier is writing about: “the worriers; the fearful; the lonely, lost and sad,” those tweens and teens who suffer from too much self-focus brought on by too many hours on the therapist’s couch.

The second and longest section of the book details problems generated by schools and parents. The parents under discussion are Gen Z mommies and daddies who wanted to raise “happy kids” and avoid the traps of their autocratic parents but instead have become fearful worriers who outsourced their parental duties to “professionals”—the teachers, therapists, and experts who turn the children into hopeless neurotics.

The horror at the center of this book is the collection of mental health surveys given to students at schools in Arizona, Missouri, Delaware, and Indiana. Shrier quotes liberally from these surveys to show just how far schools overstep professional boundaries. Some of the questions include: “During the past 12 months, did you do something to purposely hurt yourself without wanting to die, such as cutting or burning yourself on purpose?” “Do you feel very close to your parents?” “How often do your parents tell you they’re proud of something you’ve done?” “How often do parents in your family insult or yell at each other? Never (1) Not very often (2) Some of the time (3) Most of the time (4) All of the time (5).” It is fair to ask why teachers are asking children to critically appraise their family members and to share their private thoughts. You’ll want to throw the book out the window—or at the nearest school administrator.

Every chapter in Bad Therapy probably needs the caveat, “Not all therapists/schools/teachers/doctors harm children.” Surely one bad apple does not spoil the bunch. The problem, as Shrier reports, is that there is more than one bad apple in the bushel and many, many worms.

Shrier documents the many little problems that have led to this massive rot now facing parents. These problems are economic (a market flooded with therapists have monetary interests in keeping patients ill); cultural (social forces, including social media, celebrate mental illness as a sign of an individual’s authenticity); professional (the healing and educational sectors have been taken over by activists who embrace the social aims of therapeutic culture); and parental (moms and dads have subordinated themselves to “experts” who are supposed to know what they’re doing but don’t).

Eventually, readers will wonder what sort of parents are most likely to see their children emulsified by a bad therapist. Is it me?

In reality, all parents need to protect their kids from the pressure to pathologize adolescence. That isn’t easy since our therapeutic culture has valorized therapy and mental illness. Intriguingly, the parents most likely to struggle to set up an Iron Dome against charlatans are liberal-minded parents. These are the parents most likely to trust therapists and teachers, and they are the ones least likely to want to lay down firm rules that might help their children stay on course.

Shrier tells the story of Keith Gessen, a dad who strives to be nice to his children (not like one of those disciplinarians from yesteryear) and ends up feeling like a failure when his three-year-old tells him he’s a “bad dada.” “I felt he was right,” cries Gessen, “I was not a good dada. But I didn’t know what else to do.” Gessen details his self-abasement to the readers of his book, and Shrier shares these pitiful stories with her readers as an example of how parents retreat from their role as the child’s authority and end up driving themselves—and their kids—mad.

In contrast, Shrier reports that authoritarian parents (the ones Gessen wanted so badly to distance himself from) tend to raise children who are better able to survive the vicissitudes of therapeutic culture. Parents like Gessen confuse gentleness with compassion. The gentler (i.e., wimpier) Gessen became, the less secure his child felt and the more he acted out.

Love imposes limits. It is a lesson many parents have forgotten, and one Shrier reminds her readers must be retrieved.

The last section of the book offers advice to parents who, by this point in the book, are probably feeling panicked, angry, and guilty. She arms parents with research that can help them counter folklore circulating among therapists. Contrary to what kids might hear in school, trauma does not permanently alter the structures of the brain. “Body memory” is a myth. So, too, are ideas of inherited or intergenerational trauma. These dangerous diagnoses give teens reasons to indulge in endless self-study of their own supposed brokenness, when, for most of them, there is nothing all that wrong with them.

Shrier’s advice on parenting, drawn from wise people in her life, the experts she’s interviewed, as well as her own experiences as a mother, make Bad Therapy read like a self-help book and a motivational speech. Parents will need the “upper” after so many frustrating and depressing chapters about the ill health of young people.

Bad Therapy is one of a series of books trying to figure out what’s wrong with kids. Jonathan Haidt’s highly readable The Anxious Generation pins many of the problems on social media and smartphones. Johann Hari’s Stolen Focus describes an epidemic of distractedness that turns children into unproductive zombies. These and other books make bestseller lists because so many parents intuit that something has gone horribly wrong with tweens and teens. Read together, readers can start to see the larger forces working on—and working over—the teenage brain.

Elon Musk recommended every parent to read Shrier’s book. So does this reviewer. Bad Therapy offers a quick kick in the can to parents who worry they’re doing it all wrong and advice on how to help the kids who need it most.

Robert Grant Price is a university teacher and communications consultant.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!