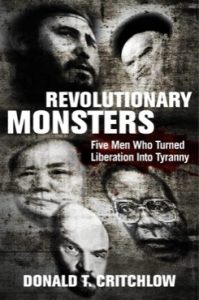

by Donald T. Crichlow.

Regnery, 2021.

Hardcover, 206 pages, $30.

Reviewed by Jason C. Phillips

“These monsters wore the masks of liberators, hiding the malevolence of hubris that comes when men attempt to create heaven on earth.” These apt words describe the mindset behind five revolutionaries who promised heaven but delivered hell for their supporters: Vladimir Lenin, Mao Zedong, Fidel Castro, Robert Mugabe, and Sayyid Ruhollah Khomeini. They brought terror and death to millions, committing atrocities throughout their lives in the pursuit of power. They are the subject of Donald Critchlow’s new book, Revolutionary Monsters: Five Men Who Turned Liberation into Tyranny. This timely book is intended to be a warning to the youth of America, who are becoming increasingly sympathetic towards what Critchlow dubs “the siren call of revolution.”

One of the strengths of Critchlow’s approach is his focus on the revolutionary mindset. The work explores the shared vision of Lenin, Mao, Castro, Mugabe, and Khomeini. This is a pivotal aspect of the work because the five monsters under investigation held quite different ideas on Marxism or economics, but they all shared the revolutionary mindset. What united them was the total pursuit of what Critchlow called the “millennialist visions of a perfected society.” While Critchlow could have paid more attention to the French Revolution and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, he does make it clear that this is where the notion of the perfectibility of man and society came from. Recently Justin D. Garrison and Ryan R. Holston edited a volume entitled The Historical Mind: Humanistic Renewal in a Post-Constitutional Age that highlights Rousseau’s influence on the problems of our age and looks to the thought of Irving Babbitt and others as a corrective to this utopian vision. I see similarities here between the willingness to suspend the traditional Christian understanding of original sin and the flawed vision of creating a new and perfected society among the revolutionary monsters. With such hubris on display, we really should not be shocked at the end results each man brought about. As Critchlow notes, “These revolutionaries shared a deep faith in the perfectibility of men. In their claim of historical necessity, they denied the lessons of history—mankind’s fallen nature.”

The revolutionary mindset is not just about a flawed vision of human nature. It also entails a willingness to strive towards that utopia regardless of the consequences. Critchlow does an amazing job chronicling the various atrocities and body counts of these five revolutionaries. A pattern emerges fairly quickly. First comes the violence of the revolution, on display as early as the French Revolution and its famous guillotine, and then the violence to protect the revolution from enemies foreign and domestic.

Critchlow shows in Revolutionary Monsters that this should be expected from these revolutions because “Modern social revolutionaries speak as liberators for the oppressed and the downtrodden. Vengeance against the oppressors is called for in the revolution. As a result, revolution becomes an act of vengeance.” This is what separates a political revolution from a social revolution. Critchlow notes the American Revolution and the successful revolutions in Poland and the Baltic as examples of political revolution; the distinction could also be made of Eastern and Central Europe more broadly in the dwindling days of Soviet power. Social revolutions are different. They are not waged over political leadership or conceptions of natural rights. They are waged to settle scores and transform society to better fit the millennialist vision of some leader. This is why they turn into acts of vengeance where people must be hurt and statues must fall. Society must be completely transformed in order for it to reach perfection, and only the messiah-like figure of the revolutionary can accomplish this task. This is the moment we now inhabit.

Nor does the violence does not stop once vengeance has been achieved. Critchlow’s book does a terrific job in showing how violence becomes a constant tool of the revolutionary monster, used to maintain power over the people and eliminate potential rivals, the primary example being Fidel Castro sending Che Guevara to his death in Bolivia. For the revolutionary monster, there is no limit to what may be done to achieve victory and protect the revolution. As Critchlow poignantly notes, “As they brought the blade of history to murder thousands, they remained confident of their self-anointed roles as the saviors of mankind. The hubris of proclaiming oneself a savior astounds the average person, but it defines the revolutionary mind.” This should be a valuable lesson for today’s youth who believe revolution is trendy or necessary.

One final note that Critchlow stresses is the cult of personality that surrounds these revolutionary monsters. While there is no question that these men were corrupted by power, it is important to remember that it was their determined belief that only they could be the saviors of mankind that propelled them to that power in the first place. This megalomania is the final piece to the mindset of the revolutionary monster. Lenin, Mao, Castro, Mugabe, and Khomeini all believed that they could lead the world in a new direction. They faced different problems, but their answers all stemmed from the same revolutionary mindset. Only this messiah could implement a Marxist-based order, rid Africa of Western imperialism, or protect Islam from Western secularism. Such power drove the creation of cults of personality. They were the sole saviors and as such their rivals within the revolution were eliminated as quickly as the supposed villains of the old order. Critchlow explores how a willfully gullible Western press helped craft these cults of personality by weaving journalists like Agnes Smedley, Edward Snow, and Herbert Matthews into his narrative. While Joseph Stalin is not covered in detail in this work, it would have been nice for Critchlow to include the naive journalist Walter Duranty to highlight even further the culpability of the Western media in these atrocities.

One of the most useful things this book does is to dig deep into some of the more overlooked flaws of these revolutionary monsters. Critchlow illustrates the anti-Semitism of the Soviet Union by bringing up Stalin’s “Jewish Doctors Plot” and offering much reflection on Khomeini’s attitude towards Jews. His book also delves into the homophobia associated with many of these monsters. For example, Critchlow cites Castro’s pejorative use of maricones (homosexuals) to refer to intellectuals and his furiously referring to Khrushchev as a homosexual for not launching a nuclear strike on the USA during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Additionally, Crichlow also digs into Robert Mugabe’s rampant homophobia. Then there are the examples of racism, including Lenin’s February 1918 massacre of 14,000 Muslims in Russian Turkestan and Mugabe’s genocidal war on the Ndebele and Kalanga peoples.

Critchlow’s Revolutionary Monsters is a great introductory study of the revolutionary mindset and how Lenin, Mao, Castro, Mugabe, and Khomeini represent it. The work is a tremendous answer to the many questions today’s youth have about revolution and socialism. The author shows how far removed these movements are from the romantic view attached to them. These aspects of the revolutionary monsters often get left behind in a focus on body counts, but this is a mistake. Those susceptible to the siren’s call of revolution need to understand that these are not movements free of the blemishes they assign to modern America and the West. Critchlow notes of his work that “The assumption behind Revolutionary Monsters is that facts can replace vacuous rhetoric about ‘liberation,’ ‘equality,’ and ‘freedom.’” Let us pray that he is correct.

As an assistant professor of history with years of teaching experience, I can attest that today’s college students have virtually no background knowledge on these five revolutionaries when they enter my world history survey courses. This book can go a long way towards showing them the problems inherent with scheming towards a utopia. I will be assigning this book to my students, paired with some of the major writings and speeches from its five major characters. The global aspect of Critchlow’s work is of the utmost importance, as Mugabe and Khomeini are even less known or understood than Lenin, Mao, and Castro. This book will serve as a wonderful foundation for my world history survey course.

Jason C. Phillips is an Assistant Professor of History at Peru State College in Peru, Nebraska. He received his PhD from the University of Arkansas in 2019 with a focus on German history, but has since changed his research direction and is currently focused on American political history. He is working on a book entitled Reagan’s Women, which explores the role Republican women played in shaping party politics and conservative debate throughout the 1980s.

Support The University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!