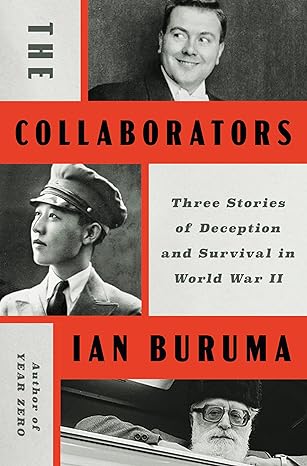

By Ian Buruma.

Penguin Press, 2023.

Hardcover, 320 pages, $30.

Ian Buruma published The Collaborators: Three Stories of Deception and Survival in World War II early last year. The University Bookman contributor JP O’Malley caught up with Mr. Buruma to discuss the writing of his latest book.

After the Second World War, a special court was established in the Netherlands to deal with cases of betrayal and Nazi collaboration. Among the 150,000 suspected collaborators awaiting trial in jail was a Hasidic Polish-Dutch Jew, the economist Friedrich Weinreb. In May 1947, Weinreb was sentenced by the special court to six years in prison for masterminding a fraudulent scheme that promised thousands of Dutch Jews an escape route from Nazi persecution.

For a large fee, Weinreb claimed he was able to arrange special trains that would take Jews from Nazi occupied Holland to France first, and eventually to neutral countries like Switzerland and Portugal. Seat numbers were allocated. Departure times were announced. Secret meetings were even held to discuss living arrangements once these Jews landed in their respective countries of safety. The exact timeline of when the fictitious train scheme began is unclear. But it is most likely that thousands of Dutch Jews signed up for it sometime in late 1941 at Weinreb’s address near The Hague, and at various addresses in The Hague, Rotterdam, or Amsterdam.

Weinreb even claimed the scheme “was sponsored by a humane high-ranking Nazi officer named Herbert Joachim von Schumann,” Ian Buruma, an acclaimed Dutch intellectual, writer, and editor explains from his home in New York. “But it was all an illusion and most of the people who gave Weinreb money ended up in death camps,” says Buruma, whose father worked as a defense lawyer in the special court dealing with Nazi collaboration in postwar Holland.

“Several Jewish witnesses [in the case] convinced the prosecutor, P. S. de Gruyter, that Weinreb’s fraud was more serious than a simple scheme to enrich himself,” Buruma writes in The Collaborators, published earlier this year. “The swindle, in the prosecutor’s view, cost lives because people’s trust in Weinreb prevented them from finding other means of escape,” says Buruma who compares Weinreb to other famous fraudsters, such as Bernard Madoff.

The Dutch writer, who regularly contributes to The New Yorker and whose previous books include The Churchill Complex (2020) and A Tokyo Romance: A Memoir (2018), gleans much of the details pertaining to Weinreb’s wartime swindling operation in the Netherlands from a report published in 1976 by the Dutch National Institute for War Documentation (now the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies). Buruma quotes occasionally too from Weinreb’s memoirs, including Collaboration and Resistance (1971).

Weinreb’s war record by the National Institute for War Documentation (RIOD), for instance, concluded that at least twenty-two people lost their lives because of Weinreb’s spying activities for the Nazis. One witness quoted in that same report claimed he had “no doubt Weinreb had been used by the SD to pump fellow prisoners for information and was sure that Weinreb betrayed many Jews who were in hiding.”

The collaborator was eventually brought to Westerbork, a transit camp in Holland that transferred Jews to death camps in Poland. There he was given an office and could enter and leave the camp whenever he felt like it. Weinreb knew there was no Jewish resistance network, but he decided to play for time until he could devise an alternative scheme. “But we must not forget that Weinreb and his family, as Jews, were always in mortal danger,” says Buruma. “One of his children, David, for example, died of pneumonia in [Westerbork].”

Weinreb used his contacts in the Nazi hierarchy to survive the Holocaust. He managed to flee from Westerbork (when exactly it’s not entirely clear) after securing a meeting with the wife of Franz Fischer, an SS officer in Holland. In 1948 Weinreb’s six-year prison sentence was halved after he received a pardon in honor of the jubilee celebrations for Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands. The controversy surrounding Weinreb’s wartime swindling operation, and further allegations against him, did not end there though.

In 1968 Weinreb was handed another prison sentence for a case of alleged sexual assault. The complaint had been lodged two years earlier by one of Weinreb’s female followers. “Weinreb was a serial sexual abuser for most of his life,” says Buruma. Weinreb escaped further jail time by fleeing to Switzerland, where he lived for nearly two decades, until he died in 1988.

In the latter part of his life, Weinreb became a famous religious guru. Most of his followers were upper class women, who turned to him for religious guidance. Weinreb claimed he had found the key to the true meaning of the sacred words through a secret code of numbers associated with the Kabbalah.

“For many decades after the Second World War, and indeed after his death, public opinion in Holland and further afield was divided over Weinreb. “Many saw Weinreb as a modern-day Dreyfus, a Jewish scapegoat for crimes committed by Gentiles,” Buruma explains.

The Collaborators also tells the story of Felix Kersten. He was the personal masseur of the Nazi mass murderer and head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler. After the Second World War “Kersten presented himself as a resistance hero who convinced Himmler to save countless people from mass murder,” Buruma explains.

Kersten’s postwar status as a heroic friend of the anti-Nazi resistance, and his acclaim in the Netherlands in particular, partially arose from a story which insinuated that he saved the entire Dutch population from being deported by the Nazis to Poland in 1941. Kersten claimed he was shown a top-secret document about the imminent expulsion of the Dutch and Flemish populations to Poland. Three million men would be forced to march to Poland through Germany. The rest of the roughly nine million people would be transported by train and ship, and then plunked amid the icy lakes and dark woods near Lublin.

“There are no documents to prove this happened, we have only Kersten’s word for it, backed up in vague and often contradictory statements made after the war by several former SS men,” says Buruma. Still, Kersten “certainly did some good, even as he played his role as a member of a mass killer’s court,” Buruma stresses. Specifically, this was Kersten’s role in a rescue mission that started in March 1945, which saw several buses from the Swedish Red Cross enter into a few concentration camps, including Dachau, Mauthausen, and Ravensbrück. After several weeks, more than twenty thousand were released from the camps, including several thousand Jewish prisoners. The rescue mission took place in total secrecy. The exact role Kersten played in the negotiations, which led to the freeing of these prisoners, is a little hazy though, says Buruma.

Nevertheless, since he was by that stage negotiating on behalf of the Swedish Red Cross, Kersten was then asked by the World Jewish Congress to set up a meeting with Himmler. It took place in the last days of the Second World War, in April 1945, at Kersten’s country house outside Berlin, between Himmler and a Swedish representative of the World Jewish Congress, Norbert Masur.

“The meeting was part of an attempt to make a deal to release many prisoners in exchange for what Hitler hoped would be a deal that was [politically] beneficial to him,” says Buruma. He claims any so-called heroic deeds Kersten undertook were done to protect his own public reputation. He knew Germany would lose the Second World War, and that his previous association with Himmler would not look good. Kersten thus decided to re-write his own history.

Buruma’s book paints a portrait of a self-serving sycophant, who despite having thorough knowledge about the horrors of the Holocaust, chose to look the other way for quite some time. Kersten died of a heart attack in Düsseldorf, Germany, in 1960 at the age of 61. Buruma claims “through the 1950s Kersten continued to help Nazis, and even pleaded with a war crimes court to treat a concentration camp doctor with clemency.”

The idea that Himmler’s masseur did not know about the genocidal program being committed against Jews by the Nazis during the Holocaust is “clearly nonsense,” says Buruma. Anne Frank, after all, had heard about atrocities that were happening to Jews in Poland on the BBC radio as early as 1942, Buruma stresses. “If a teenage girl locked up in an attic in Amsterdam already knew about this information, how could it be that [Kersten] who was travelling around eastern Europe with Himmler on a private train, could not have known? It’s impossible.”

JP O’Malley is an Irish writer living in London.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!