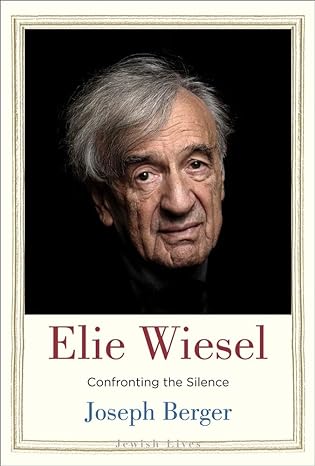

By Joseph Berger.

Yale University Press, 2023.

Hardcover, 360 pages, $26.

Joseph Berger published Elie Wiesel: Confronting the Silence early last year. The University Bookman contributor JP O’Malley caught up with Mr. Berger to discuss the writing of his latest book.

Elie Wiesel was born into a small traditional Hasidic community on September 30, 1928, in Sighet, located in the Carpathian Mountains of Transylvania in East Central Europe. “Before the torment it was a little Jewish city…with beauty and faith,” as Wiesel put it in The New York Times in 1984. The Romanian-American author was referring to the cleansing of Sighet’s Jews in May 1944, when the city was part of Hungary.

Most were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Wiesel was among the deportees. So too were his parents, Shlomo, and Sarah, and his three sisters, Hilda, Beatrice, and Tzipora. Upon arrival to the infamous concentration camp in Nazi-occupied Poland, his family members “were separated between those destined for immediate death in its gas chambers and those sent to work as slave laborers,” Joseph Berger writes in Elie Wiesel: Confronting the Silence, which was published in May of last year.

“I was inspired to write this biography because I felt it would allow me to humanize Wiesel,” the Russian-born American author explains from his home in Westchester County in New York. Berger uses Night (1960) as a guide to tell the first part of this monumental life story. Wiesel’s memoir, which sold ten million copies, documented the eleven months he spent as a young teenager in three respective concentration camps: Auschwitz, Buna, and Buchenwald, near Weimar, Germany.

The biographer begins the book by exploring the relationship Wiesel developed with his father, Shlomo, while both were Nazi prisoners. “Their relationship had been distant for some time, but then when they were together in the camp, Wiesel felt he had to protect his father, who couldn’t withstand the work, or the brutal beatings,” Berger explains. “And so the roles were reversed and Wiesel had to take care of his father.”

Wiesel never received any official explanation from the Nazi authorities regarding how or why his father died in Buchenwald. He woke up one morning and Shlomo had vanished. It’s most likely his body was taken to the camp crematorium. “No prayers were said over his tomb. No candles lit in his memory,” was how Wiesel explained the sudden and mysterious death in Night.

In April 1945, Buchenwald was liberated by the United States Third Army. After the war, Wiesel met with his sister, Hilda, in Paris. She informed him that Beatrice had also survived. The three siblings briefly met in Antwerp, Belgium, but avoided talking about Tzipora or their parents, all of whom had perished in captivity.

By the late 1940s, Wiesel had enrolled at the Sorbonne University, Paris, where he attended lectures by world famous writers and philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Buber. “These years in Paris were crucial in ensuring that Wiesel became a cultivated intellectual,” says Berger, whose previous books include Displaced Persons: Growing up American After the Holocaust (2002) and The Pious Ones: The World of Hasidim and Their Battles with America (2014).

In the Spring of 1948 Wiesel got a job in Paris working as a translator for Zion in Kampf. The Yiddish weekly was a propaganda mouthpiece for the militant Jewish terrorist underground resistance movement, the Irgun. A year later, the rookie journalist was sent by the French newspaper, L’Arche, to report from what was then a newly established state of Israel. Wiesel felt many Israelis he encountered at that time had little sympathy for Holocaust survivors from Europe. In his view, they were offered housing and commiseration from the Jewish state, but little sympathy or respect, says Berger: “The Elie Wiesel the world came to know, the champion of survivors, the orator and writer who explained their story to the world, in ways that honored, not depreciated, their war time ordeals, was born on that trip to Israel.”

By his mid-20s, Wiesel had become a well-respected journalist. He wasn’t making a great deal of money. But his credentials gave him opportunities to travel widely. Wiesel reported from Brazil, Spain, Morocco, Argentina, and the United States. The latter country became Wiesel’s adopted homeland in 1956, after he was appointed New York correspondent for Israeli national daily, Yedioth Ahronoth.

“It was in New York that Wiesel really developed his confidence as a writer,” says Berger. The biographer also notes that in addition to his work with Yedioth Ahronoth, Wiesel began freelancing for The Jewish Daily Forward, then the most widely circulated Yiddish newspaper in the United States. He also mixed with a whole host of writers in the New York literati, including Isaac Bashevis Singer, Irving Howe, Hannah Arendt, and Norman Podhoretz.

Wiesel could read and write in English, French, Hebrew, and Yiddish. But he never lost his love for the latter language, says Berger. “Wiesel savoured the quirks and flavours of Yiddish and loved to sing Hasidic Yiddish melodies,” he says.

Wiesel also documented his experiences of Auschwitz and Buchenwald in his mother tongue. When exactly he first committed the story to paper remains a bit of a mystery, largely because Wiesel gave two accounts, with two different timelines.

In the first version, Wiesel supposedly began writing Night within weeks of liberation, while in the Buchenwald hospital recovering from food poisoning. The second version says he wrote Night on a voyage to Brazil in 1954. Either way “the Yiddish version of Night was brought forth on that voyage,” Berger explains. “And in 1956 the first Yiddish version of Night was published in Argentina, under the title And The World Was Silent.

The English version of Night appeared in 1960 and eventually catapulted Wiesel to international fame. A short novella, Dawn, appeared the following year. The New York Post serialized the novel and also ran a profile of Wiesel. The public platform gave him an opportunity to convey to a broad audience his views on the Holocaust. The timing of the interview also coincided with the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem, which Wiesel covered for The Jewish Daily Forward.

His account of the trial was quite different from the version presented by Hannah Arendt. The German Jewish intellectual wrote about it for the New Yorker, which eventually yielded the infamous “Banality of Evil” essay. “Wiesel found Arendt remote, condescending, and lacking in feeling for the millions of Jewish dead,” says Berger. “He also pointed out that Arendt did not attend many of the sessions of Eichmann’s Jerusalem trial, even though she wrote these very [controversial] pieces for the New Yorker that evoked images of Jews going to their deaths like sheep to a slaughter.”

Wiesel explored this issue with much more sensitivity and complexity in several personal polemics he wrote. In an essay he published in the 1960s entitled “A Plea for the Dead,” Wiesel contemplated why so many individuals within his own Jewish community in Sighet (including his own immediate family members) were overcautious, indecisive, in denial, and incredulous before being sent to death camps.

Berger’s biography also points out that Wiesel, at least for some time, made several attempts to criticize Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. In 1974, for instance, Wiesel delivered a speech to the governors of the Jewish Agency in Jerusalem, where he asked, “Are we wrong to ask you to adopt a more Jewish attitude towards Palestinian Arabs?” The audience and the Israeli media, however, did not take his criticism lightly. Specifically, it focused on Wiesel’s firm “belief that Palestinians living in the West Bank after the Six Day War in 1967 were witnessing their land being occupied by Israeli settlements,” says Berger.

“When Wiesel made that statement in 1974 in Jerusalem, it resulted in a very critical response from many Israelis, who said: who are you to tell us how to treat the Palestinians, you don’t know what it’s like to live in Israel, in a dangerous situation,” Berger explains. “Wiesel was so upset by the Israeli reaction that he made a pledge to himself never to criticize Israel again. And he never did.”

The biographer points to the hypocrisy in taking such a stance, however. Despite his reputation as a global spokesman against genocide and crimes against humanity, Wiesel could be selective about what atrocities actually mattered. After Israel invaded Lebanon in 1982, Lebanese militiamen from the Christian Phalangist movement embarked on an orgy of rape, murder, and mutilation in the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila in Beirut. Israeli soldiers were not directly involved in the massacre. But they stood by and did nothing to intervene. Wiesel was berated by many liberals at the time. “They felt he could have been tougher on Israel on this issue and explicitly reproached its leaders and generals, but instead he chose not to make a public fuss,” says Berger.

Wiesel refused to keep silent, however, at the White House on April 19, 1985. As chairman of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council, he publicly criticized then U.S. President Ronald Reagan, who chose to lay a wreath in Bitburg cemetery where Nazi soldiers were buried. The visit was supposed to help strengthen ties between the United States and West Germany during a tense moment of the Cold War. Wiesel’s criticism came two weeks before Reagan was to leave for his trip to West Germany. Wiesel had been named as a recipient of the prestigious congressional Gold Medal, for preserving the memory of the Holocaust. “At the ceremony in [the White House] Wiesel told Reagan, in a very humane way, “that place [in Bitburg cemetery] is not your place, Mr President, your place is with the victims.”

“That was a very important moment and Wiesel made sure that among his guests that day [in Washington D.C.] was the executive editor of the New York Times, Abe Rosenthal and the managing editor, Arthur Gelb,” says Berger. “So it became widespread international news and helped elevate Wiesel’s stature from an important figure among the Jews of America to a worldwide figure.”

A year later, Wiesel was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace for “being a messenger to mankind.” Berger believes Wiesel’s respectful, but controversial, confrontation with President Reagan “goaded the Nobel prize committee to pick Wiesel as the prize winner.”

Just hours after he received the prestigious accolade, Berger interviewed Wiesel for the New York Times, asking him how he could continue to believe in a God who allowed most of his family, and millions of his people, to be slaughtered. “I have not answered that question, but I have not lost faith in God,” Wiesel replied.

“Many of Wiesel’s supporters often looked at him as someone who had the aura of a prophet,” says Berger. “But I was always struck by his generosity and his very human qualities, he was always very kind and very approachable.”

Elie Wiesel died at age 87 at his New York home on July 2, 2016, surrounded by his wife, Marion, and his son Elisha. That day, President Obama tweeted that Wiesel “was a conscience for our world.” Berger agrees. “[Wiesel] seared the Holocaust into the world’s conscience, compelling everyone to confront the human capacity for brutality and evil,” he concludes.

JP O’Malley is an Irish writer living in London.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!