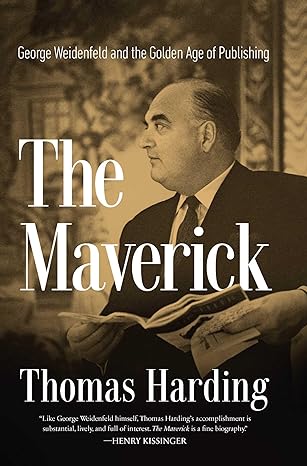

By Thomas Harding.

Pegasus Books, 2023.

Hardcover, 336 pages, $29.95.

Thomas Harding published The Maverick: George Weidenfeld and the Golden Age of Publishing last year. The University Bookman contributor JP O’Malley caught up with Mr. Harding to discuss his writing of the first biography of this important figure.

Thomas Harding’s latest book, The Maverick, begins on September 13, 1919, in Vienna, where Arthur George Weidenfeld was born. He was the only son of Max and Rosa Weidenfeld and grew up in a modest middle class Jewish family. Researching the biography, Harding travelled to the apartment where George Weidenfeld and his family lived. Gumpendorferstrasse 111 was once a bustling Jewish neighborhood within Vienna’s 6th District. “I wanted to find out about George’s life before he came to England, so I met George’s daughter, Laura, who kindly sent me this diary, which his mother had kept when George was a small boy in Vienna,” Harding explains from his home in Hampshire, England.

The award-winning, bestselling author, whose previous books include Hanns and Rudolf (2013) and The House by the Lake (2015), notes how Weidenfeld as a child was taught how to read Hebrew and encouraged to pay attention to his family’s religious heritage. On his mother’s side of the family there were Jewish rabbis going back to the sixteenth century. Weidenfeld learned from his mother about the most famous of these: Isaiah Abraham Horowitz (also known as the “Holy Shelah”). Horowitz had been chief rabbi in Prague before moving to Jerusalem where he led the Ashkenazi community. During his time in Israel, Isaiah Abraham Horowitz wrote a book that became highly influential among European Jews. In it, he stressed the pursuit of joy and positivity, even in the face of adversity and evil.

It’s an attitude that Weidenfeld would embrace for most of his life. He would later lose both of his grandmothers in the Holocaust. He never spoke about the trauma for the rest of his life, even to his own family. Harding points out that Weidenfeld managed to exit his home city, Vienna, at the right moment. Nazi Germany annexed Austria in March 1938. Weidenfeld arrived in London the following summer. “George came to England with no contacts, no money and could barely speak English,” Harding explains. “But through hard work, diligence, and skills, he was able to build this extraordinary publishing empire.”

Weidenfeld was just twenty-years old when he landed a job as a linguist for the BBC’s Overseas Intelligence Department. The work introduced him to figures like English novelist George Orwell, the exiled leader of the Free French General Charles de Gaulle, and a young writer called Nigel Nicolson.

The latter figure came from a bohemian background with old money. His family also had good social connections, particularly in the literary world. Both proved useful when the two young men launched a publishing house in London in 1949. Weidenfeld & Nicolson would go on to publish numerous best-selling authors, including Henry Kissinger, Joan Didion, Henry Miller, Edna O’Brien, Clare Tomalin, and Saul Bellow. The London publisher also published books by senior Nazis.

Included in Weidenfeld & Nicolson’s 1953-54 catalogue, for example, was Hitler’s Table Talk, a series of monologues given by the Führer. The book was edited by the Oxford academic Hugh Trevor-Roper, who added an introduction, providing context and historical background. In that same catalogue was The Story of Nazi Political Espionage by Wilhelm Hoettl, which provided an insight into the German secret service. Then in 1970 Weidenfeld & Nicolson published Inside the Third Reich by Albert Speer. In 1942, Speer had been appointed Armaments Minister in Hitler’s government and became second only to Hitler himself as a power on the home front. For publishing these controversial titles, Weidenfeld was repeatedly attacked by Jewish individuals and organizations. He was also criticized for providing a platform for Nazis and for amplifying their propaganda.

Harding speaks about the great lengths Weidenfeld sometimes had to go to get these authors published. This was particularly true of Speer who was incarcerated in Spandau prison after the Second World War. Weidenfeld wrote to him, suggesting that he write his memoirs. “Speer was released in 1966 after completing his twenty-year sentence and, soon after, George hosted a dinner party for him in Düsseldorf with a group of influential people, including British and German diplomats and journalists,” Harding explains.

The English author confesses that he was commissioned to write this biography by the current chairman at Weidenfeld & Nicolson. “I made it clear to the publisher from the beginning that they had no control over anything I wrote on this book,” Harding insists. “And I can honestly say they haven’t asked me to keep anything out.”

Harding doesn’t appear to self-censor though. Nor does he go out of his way to paint Weidenfeld in a favorable manner. “I think George was somebody who was totally self-serving,” says Harding openly and honestly. “He was a very lonely character and he tried to compensate for that by forging this network of friendships and business partnerships. Books and publishing became his way of achieving that.”

Many of the books Weidenfeld & Nicolson published are now considered modern classics. Among those titles are The Double Helix (1968) by James Watson and The Group (1963) by Mary McCarthy, as well as huge bestsellers, such as Keith Richards’s memoir Life (2010), Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy (1993), and I Am Malala (2013) by Malala Yousafzai.

“Just look at how many extraordinary books that were published under George’s guidance as co-founder of Weidenfeld & Nicolson,” Harding points out. “You can say after one or two, that maybe he was lucky. But when you start getting into roughly 30 or 40 books that changed modern western culture, you have to start thinking, this was a man who had the ability to recognize literary greatness.”

Weidenfeld personally took on huge financial risks to get some of the more controversial titles he took on published. This was especially true of Lolita (1955). Originally published in Paris by Olympia Press, Vladimir Nabokov’s novel recalls Humbert Humbert’s steamy romance with a twelve-year-old. Is it literature? Is it pornography? It is undoubtedly about a middle-aged man who repeatedly rapes a teenager he purports to be smitten by.

These issues were raised in the lengthy debates that ensued in the months leading up to Lolita’s publication in Britain. They were even featured in Britain’s House of Commons. Over the summer of 1958, Conservative chief whip, Ted Heath, begged Nigel Nicolson, then a Tory MP, not to publish the book. In mid-December 1958, a week before a new Obscenity Bill was being debated in Westminster, Nicolson addressed Parliament about the importance of artistic freedom and the dangers of censorship. “Is an obscene work of art a contradiction in terms?” he asked his fellow MPs rhetorically. In the winter of 1959, amid much scandal and media fanfare, Weidenfeld & Nicolson published Lolita. Within weeks nearly 300,000 copies were sold in Britain and across the commonwealth.

The publishing of Lolita changed the ability for writers to be able to publish what they felt was important to write, the biographer explains. However, “Nigel Nicholson’s family was against the publication of Lolita, so Nigel was caught between his parents and George on this issue,” says Harding. “And he stood up for the publication of the novel in the British Parliament and lost his constituency seat [as a result of it].”

The biographer spends considerable time and ink looking at how Weidenfeld used his publishing empire to wield political influence. In 1949, Weidenfeld worked in the office of Israel’s founding president, Chaim Weizmann. He also published the memoirs of some leading Israeli politicians, including Golda Meir, Shimon Peres, and David Ben-Gurion. “George was an ardent Zionist before the state of Israel was created in 1948,” Harding explains. “And like many Jews of his generation, that only strengthened after the Holocaust.”

Harding says Weidenfeld had a “long, involved and complicated relationship with Israel.” “At times, some people, particularly his authors, criticized George for prioritizing Israel over other aspects of his life,” the author points out. “His relationship with Israel was not without controversy, certainly in the publishing world.”

The biographer also notes that after the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, Weidenfeld became increasingly preoccupied with European politics and the issue of German unification. Weidenfeld felt a unified Germany would be beneficial to Germany itself, Europe, and the world.

In a letter to Helmut Kohl, the chancellor of West Germany, dated February 23, 1990, Weidenfeld made clear his reasons for supporting reunification. “A united Germany can and must play a vitally important part, not only politically and economically, but also in the sphere of human rights, and especially in the struggle against racism, chauvinism and anti-Semitism, as it helps the emergent democracies of Central and Eastern Europe to enter the civil society,” he wrote.

On July 13, 1990, Weidenfeld met Kohl for two hours at his home in Bonn. The following day Weidenfeld summarized his thoughts on paper. “Germany’s auspicious progress on the road to unity is not only a vindication of the Federal Republic’s achievement in building a functioning democracy, vibrant economy and civil society but also renews a link with all that was most promising in the early part of the Weimar Republic and in the past century.”

Germany finally reunified in October 1990. Eight months later, Weidenfeld received the Knight Commander’s Cross (Badge and Star) of the Order of Merit from the newly united German government.

“George would always say that he was somebody who loved both Germany and Austria,” Harding explains. “But he loved them before the Nazi regime. And he wanted to be part of bringing that back. For George it was about rebuilding a culture that he found really beautiful.”

“But his relationships with Germany and with Austria were always focused on another agenda: strengthening the alliance between Austria, Germany and the state of Israel,” Harding explains. “And in this regard, he was very successful.”

Elsewhere, the biographer examines Weidenfeld’s dramatic love life. He married four times and had numerous affairs. Weidenfeld first walked down the aisle with Jane Sieff in 1952, who gave birth to a baby girl, Laura, the following year. The couple divorced in 1956. Soon afterwards the publisher became obsessed with English memoirist Barbara Skelton. She was then still married to the famous novelist Cyril Connolly, who was on the books of Weidenfeld & Nicolson. Skelton left Connolly. But her marriage to Weidenfeld in August 1956 was disastrously short lived. Weidenfeld’s third marriage to American heiress Sandra Payson Meyer ended amicably after a decade. Then in 1992, aged 72, Weidenfeld tied the knot with Annabelle Whitestone. They remained married until Weidenfeld’s death in 2016. He was buried in the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, Israel.

Most obituaries described Lord Weidenfeld of Chelsea as a pillar of the British Establishment. In 1995, American interviewer, Charlie Rose, called the Austrian born British publisher a “people collector.” A polite way of describing a self-serving chameleon? Perhaps.

Many friends and foes quoted in Harding’s book take that view. They use unflattering terms like “loathsome,” “appalling,” and “monstrous” to describe an egomaniac driven by vanity and money. The biographer also cites interviews from countless women who worked for the publisher. Some remember a charmer and a seducer. Others found him “creepy and inappropriate,” says Harding. Moral imperfections aside, the publisher’s cultural legacy is secure.

The numerous books that George Weidenfeld helped publish “transformed western culture and have stood the test of time,” says the biographer. “George was both a publishing genius, but also flawed as an individual,” he says. “This was one of my main motivations for exploring his life with this biography,” Harding concludes. “That paradox between George’s external presentation and his internal reality.”

JP O’Malley is an Irish writer living in London.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!