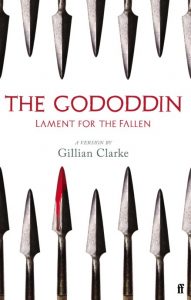

Translated by Gillian Clarke.

Faber & Faber, 2021.

Hardcover, 144 pages, $19.95.

Reviewed by David J. Davis.

At the end of the sixth century, a Celtic British tribe known as the Gododdin met an army of invading Angles at the Battle of Catraeth. The only record of this battle, the Welsh poem Y Gododdin written by the poet Aneirin, details the tragic annihilation of the native army.

Catraeth was not a disaster turned to ultimate victory. It is not like the Battle of the Alamo or the Battle of Thermopylae. Angles, Saxons, and Jutes established kingdoms across England until only Scotland, Wales, and Cornwall remained independent. Catraeth was one in a long line of battles that Celtic tribes lost to a long-term migration of Germanic peoples.

Aneirin’s original poem survives in a single 13th century manuscript known as Llyfr Aneirin (or The Book of Aneirin). Like other early Welsh poems, Y Gododdin is not a developed narrative, in the style of the Iliad. Instead, Y Gododdin reads like a highlight reel of Brittonic warriors, honoring their martial reputations, the number of bodies they left on the field, and the bloody manner in which each of them died. One of these warriors, Bradwen, is even remembered for being “worth three men” to the women in his life.

These poetic snapshots of the warriors are held together by the Welsh device known as a cynghanedd along with opening phrases like “Flaunting a brooch,” “Men rode to Catraeth,” “For the war, the ruin, the sorrow,” and “Three hundred gold-torqued men.” Within this framework, Aneirin weaves together images of the domestic and the brutal, the everyday and the awful through a complicated web of internal and end-rhyme schemes.

Gillian Clarke’s translation The Gododdin: Lament for the Fallen demonstrates a deep respect for the poem’s complexities and the linguistic gulf between Welsh and English. A former National Poet of Wales, Clarke brings the rhythms of English to bear on the original text. The end result is a decidedly English song derived from a Welsh one, which favors simple, straightforward word choice and rhymes inspired by Shakespeare and Chaucer. Clarke’s verse moves easily between playful moments like “Fickle fitful, boisterous, brash, / moody, broody in the clash” and more intense lines like “On the field of blood his blade / slashed, sword on sword.”

Clarke also reframes how the poem looks on the page, introducing visual aids, like stanzas, which do not exist in the original manuscript. These devices help modern readers, who no longer sing the verses aloud, but quietly read the poem to themselves. As Clarke explains, “what we see is what we hear.” Thus, verse 66 in the medieval manuscript stands as six unbroken lines, while Clarke has divided the verse into three stanzas, providing visual indication of the poem’s pace:

A rousing rhyme for war-bound men

in the genial small world of a hall.

He yearned the praise of poets,

revelry, horses, gold, and wine,

praise after war, should he return,

by bloodstained men for Cynddilig Aeron.

Unlike earlier translators of Y Gododdin, Clarke respects the music of the poem. She recognizes that poetry is not merely the images and meanings that words convey. Poetry is the pacing, the words, the cadences, and the harmony. Even Aneirin’s simple recitation of names takes part in this music. Unfamiliar, and unusual, names like Cynon, Buddfan, Cynwal, Tudfwlch, Gwrhafal, Bleiddig, and Gwawrddur sing of another world that we only catch blurry glimpses of. Other names like Arthur and Myrddin (Merlin) are more familiar, reminding us that this poem is not entirely isolated from the rest of the Western tradition.

Clarke’s work allows us to enjoy Y Gododdin as a poem and to be swept up in the song. This is perhaps the translation’s greatest virtue. For whether we are reading the Epic of Gilgamesh, Sappho’s love poems, or Langston Hughes’s tunes dripping with jazz, all poetry “exists to enchant,” as Dana Gioia explains. Poetry’s power to stir us, exciting the imagination and inspiring us in ways other languages cannot, is the reason we read and write poetry.

Moreover, good poetry serves us when reason and understanding fail. G.K. Chesterton noted, “The poet only asks to get his head into the heavens. It is the logician who seeks to get the heavens into his head.” This is why writers like Boethius, Hildegard, and Dante turned to verse when they faced things beyond their comprehension. Human reason is paltry in the face of the betrayal of friends, the rapture of love, the destruction of a city, the joy of victory, the erosion of cultures, and the divine encounter.

Y Gododdin does not seek to understand what happened or even why it happened. Under the darkness of utter defeat, Aneirin hails the warriors who died. In fact, Clarke’s description of Y Gododdin as a lament is perhaps her only significant misstep. It seems to be an attempt to explain, to rationalize, to grasp what Aneirin meant in writing the poem. However, it is evident that Y Gododdin is much more than a lament, if it is a lament at all.

The Gododdin has almost nothing in common with melancholy war poems like Wilfred Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est”. Certainly, Aneirin is saddened, and he blames the drinking and feasting that preceded the battle. The mead, however, is described as “poison” not because they fought but because they lost. Aneirin celebrates the brutalities of war and takes every opportunity to commemorate the virtues of violence. He calls the fallen warriors battle-bulls, eagles, war hounds, boars, and bears. When they die, it is a badge of honor that their bodies feed the ravens.

Such descriptions remind us of the distance between us and Aneirin, and they should not be subsumed by a modern view of warfare that sees the violence as lamentable. If The Gododdin is a lament, it is one that is quickly followed by the raising of steins and horns, by shouts of soldiers, hungering for more.

Nevertheless, Clarke’s translation gives much more than it takes away. Clarke reworks one of the most significant early Welsh poems into a modern song that anyone can appreciate. She reminds us that poetry must first and foremost move its readers, must cast a spell of words and rhythm that incites our passions and our imaginations.

David J. Davis, Ph.D., is Associate Professor of History at Houston Baptist University.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!