Edited by Robert Asch.

Saint Austin Press, 2021.

Hardcover, 544 pages, $39.90.

“And who shall say, that to know the great Masters is not the first necessity of an artist? Yet we might think, that a true man of letters would eagerly explore all tracts and byways of literature” —Lionel Johnson

Reviewed by Martin Lockerd

The name Lionel Johnson is inextricably linked with Decadence, a loosely organized movement that took place in Britain, primarily in the 1890s, and found its most poignant manifestations in novels such as Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, the provocative black-and-white art of Aubrey Beardsley, and the poetry of men such as Ernest Dowson, John Gray, and, of course, Johnson. On the surface, decadent art is about wine, women, song, depression, diabolism, and art for art’s sake. It is also a deeply Catholic movement, boasting more Catholic converts than any movement in British literary history.

In the past ten years, scholars of Decadence, under the usual academic pressure to divest themselves of dead white males (Oscar Wilde generally survives the cull because he invented the modern homosexual) have largely set Lionel Johnson aside. Their loss, it seems to me, is our gain. As Robert Asch points out in his 65-page introduction—the best primer on Johnson’s life and work I have ever read—Johnson may have had a decadent phase, but the decadent glove fits him poorly. His diverse corpus demands a more diverse, and perhaps less academic, readership.

Born into a respectable military family in 1867, Johnson broke the mold by not entering the service, an understandable state of affairs given that the diminutive young man never grew past five foot three. He attended the best schools and loved them. Winchester and Oxford live in his work as places of refuge, enchantment, and inspiration. He quickly distinguished himself as a thinker, poet, and eccentric, though, as Asch points out, these eccentricities were often exaggerated as part of the formation of the posthumous Johnson myth.

Johnson was a walking paradox: a childlike sage, a morally sensitive alcoholic, a thoroughly English Celt, a decadent Catholic. He associated with and admired Wilde but disavowed the man when Wilde’s life began to imitate his art too closely. He was clearly gay, to use the limited modern taxonym for sexual desire, but seems to have opted for a life of lay celibacy leading up to and following his conversion to Catholicism in 1891. Death came prematurely in the form of a stroke about a decade later. It would be trite to note that, had he lived, Johnson might have eclipsed his contemporaries. It would be true to say that what he left behind deserves greater attention.

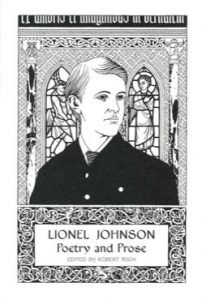

Mr. Asch’s anthology is far more than a collection of public domain texts prettily repackaged (though the book is very handsomely bound and designed, complete with ribbon marker, contextualizing images, and superb dust jacket art by Daniel Mitsui). As Joseph Pearce rightly points out in his introduction to the book, this is a work of profound and diligent scholarship. Aside from finding, reading, and compiling Johnson’s poetry, essays, and correspondence, Asch has provided footnotes that make Johnson’s work immediately accessible to the uninitiated reader. Anyone editing the work of Johnson’s more recognized contemporary and friend, W. B. Yeats, could do so tolerably well from an armchair with the assistance of an internet search service. Lionel Johnson: Poetry and Prose is a scholarly work of the old school that clearly demanded a staggering amount of labor.

Johnson’s poetry makes up the heart of the collection. It could be tempting to classify Johnson as a “religious poet” given his pervasive interest in matters of the soul and the sheer number of poems that deal explicitly with Catholic matters. T. S. Eliot disliked this classification in general on the grounds that it usually delineates a poet who is “leaving out what men consider their major passions, and thereby confessing his ignorance of them.” Even a casual reader of these poems will notice that they never shy away from the major passions. In fact, Johnson’s poetry strikes me as distinct from our age in its willingness to tackle the big questions of existence. His subject is life. His life, unlike that of so many poets of the last few decades, involved a soul. For this reason, he could speak coherently about desire (“The Dark Angel” / “To Passions” / “Mastery”), history (“By the Statue of King Charles” / “Cromwell” / “Ireland”), and death (“Pax Christi” / “In Memory” / “Nihilism”), among other things.

Johnson could be enchanted and romantic in a refreshing manner foreign to postmodern sensibilities. The narrator of Evelyn Waugh’s great decadent Catholic novel, Brideshead Revisited, identifies a young Lieutenant Hooper as the totem of an anti-romantic modern generation: “Hooper was no romantic. He had not as a child ridden with Rupert’s horse or sat among the campfires at Xanthus-side; at the age when my eyes were dry to all save poetry … Hooper had wept often, but never for Henry’s speech on St. Crispin’s day, nor for the epitaph at Thermopylae.” Not so Johnson. Poems such as “Mystic and Cavalier” and “Oxford” reveal what it means to feel to the point of tears and express that feeling with the unsentimental precision of a true craftsman of language. Anyone tired of the bloodless sentimentality and unskilled drag-prose of much of what passes for poetry today will enjoy exploring this anthology at length.

Following his Oxford years, Johnson dedicated extensive time to prose. Essays on matters as diverse as “The Imitation of Buddha,” “Huysmans’ En Route,” and “The Gordon Riots” shine with originality of thought and cultured pugnacity. He was ruthless in decrying bad popular writing: “Silly petulance, ill-bred ostentation, unfathomable conceit, offensive vulgarity, and no trace of affection or of thought: these are the gifts and qualities which we are called upon to study and to admire”; he was generous in celebrating the achievements of Edmund Burke: “Never did statesman bring to a practical mastery of facts so vast a power of poetic and philosophical imagination, so great a command of moral vision”; he was humane in appreciating the good things in life: “The Dickens feeling for Christmas, so ridiculed by some … is the true feeling of fellowship, of cordiality, of taking the earth and heaven home to heart, of sharing the fireside with them”; he was allergic to bad manners: “Let us speak plainly, and without hesitation; a gentleman does not write like that, a scholar does not write like that, a critic does not write like that.” Put simply, his essays are a delight.

The correspondence gives a welcome sense of the artist’s personal life. A young Johnson writes admiringly to his idol Walt Whitman and charmingly to his friend George Santayana. The budding public intellectual offers support to Yeats and stays in regular contact with Sir Edmund Gosse. The constant friend gives heartfelt condolences to those who have lost loved ones. The struggling alcoholic promises his aggravated landlord to take the pledge. It is a good selection.

I groped my way to two minor shortcomings that scarcely mar this excellent book. One: Asch overindulges in footnotes in his introduction. Several pages are more taken up with footnotes than main text. This tendency creates some whiplash for the reader that is not always outweighed by the added knowledge and insight contained in the notes. Two: The introduction at times seems more interested in Johnson as a Catholic convert than in Johnson as an artist. Still, I prefer this tendency over the common academic practice of sweeping matters of religion under the rug entirely.

Lionel Johnson: Poetry and Prose presents the story of an artist who did far more than pen one excellent poem about the burdens of decadent desire (his widely anthologized “The Dark Angel”). The artist contained in this book unites the relentless spiritual curiosity of John Henry Newman, the erudition and taste of Walter Pater, the boisterous wit of G. K. Chesterton, the Celtic enchantment of the early W. B. Yeats, and the earnest but disciplined poetic voice of a true classicist. I do not expect that Johnson will ever receive the attention afforded to these other names, but this anthology makes a convincing argument that he deserves a great deal more.

Martin Lockerd is an Assistant Professor of English at Schreiner University in the beautiful Texas Hill Country, where he lives with his wife and three daughters. His scholarship has appeared in the Journal of Modern Literature, Modern Fiction Studies, the Yeats/Eliot Review, and Logos. His monograph, Decadent Catholicism and the Making of Modernism, was published in 2020 by Bloomsbury.

Support The University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!