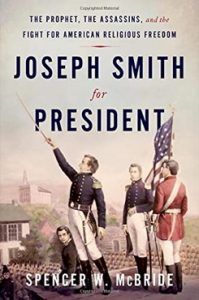

by Spencer W. McBride.

Oxford University Press, 2021.

Hardcover, 269 pages, $30.

Reviewed by John Bicknell

America in 1844 was a religious place. But it was not, in the broadest sense, religiously tolerant. The guarantees of religious freedom included in the First Amendment remained more aspirational than practical. Religious minorities were routinely victims of discrimination, and frequently targets of mob violence.

Most Americans were secure in the belief that their nation was a Protestant nation. Even those who represented the political and religious elite, such as the Whig Party’s 1844 vice presidential candidate Theodore Frelinghuysen, often professed religious tolerance while associating with organizations that were virulently anti-Catholic.

While Catholics posed a particular political problem for the Whigs in that they tended to vote Democratic and gathered in large numbers in Eastern cities where bloc voting could sway a state, Mormons posed a different sort of challenge to the broader political system.

That challenge is at the heart of Spencer W. McBride’s excellent Joseph Smith for President: The Prophet, the Assassins, and the Fight for American Religious Freedom.

The “simplistic, celebratory accounts of the country’s founding cement the misguided notion that the disestablishment of state churches during the years that followed the revolution and the protection of religious expression in the Bill of Rights brought about universal religious freedom,” writes McBride, associate managing historian of the Joseph Smith Papers Project.

But that ideal was far from reality in antebellum America, as the members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints could well attest.

The gathering of Zion that had taken place in Nauvoo, on the banks of the Mississippi in western Illinois, had created a theocratic kingdom in which the movement’s founding prophet, Joseph Smith (1805–1844), wielded both civil and religious authority and—more to the point for McBride’s story—led his flock back and forth between support for the two major political parties based not on some grand ideological theme, but on what each party would promise to do for his voters. That’s a common-enough occurrence today; minority, ethnic, and interest groups routinely vote overwhelmingly for one party or the other. In the 1830s and ’40s, it inspired fear and resentment among the Protestants of surrounding counties who worried that this new, odd religious sect was going to dominate local politics.

The Mormons, of course, had their own well-justified fears. Those fears led to an insularity that created an insular solidarity, but would eventually prove dangerous.

When the growth of Mormon settlements in western Missouri had threatened to upend the political balance there, gentile residents reacted violently. Mobs attacked Mormon settlers, and the governor issued an “extermination order” threatening the lives of those who refused to flee the state. Smith was arrested, and the Mormons, who had fled Ohio for Missouri, were on the move again, this time to Illinois.

Smith would eventually rejoin them on a swampy spit of land jutting into the Mississippi that he renamed Nauvoo. The settlement flourished as thousands of Mormon converts flocked to the growing city, which became the second largest in the state.

But Smith wasn’t done with Missouri. He appealed to the federal government for compensation, arguing that mob violence incited by state officials could have no other redress. A visit to President Martin Van Buren and to the Illinois congressional delegation won him no satisfaction. The lesson Smith took away from the experience was that Mormons needed to look out for themselves.

And so he created what historian Benjamin Park called in a recent book the Kingdom of Nauvoo, where manhunters from Missouri and Illinois sheriffs would be powerless to serve extradition papers or arrest warrants. In large part, the state of Illinois went along with the experiment, at least at first.

By 1843, around the time Smith and other church leaders had quietly begun practicing plural marriage and expending considerable energy in trying to keep the practice a secret, the political situation was as tenuous as ever. As had happened in Missouri, non-Mormons in surrounding communities were growing resentful, and the practice of polygamy was simultaneously causing unrest within Nauvoo as the “secret” began to leak out. Repeated attempts by officials in surrounding jurisdictions to get at Smith for one alleged offense or another failed when the Nauvoo courts, empowered by a state-approved municipal ordinance, tossed their cases.

But the continued attempts worried Smith, and he still hoped to invoke the power of the federal government to obtain justice for the wrongs of Missouri. As part of that quest, he wrote letters to five men likely to be presidential candidates in 1844—Henry Clay, Lewis Cass, John C. Calhoun, Richard M. Johnson, and Martin Van Buren—asking what their position would be toward ensuring the Mormons’ civil rights. Cass, Clay, and Calhoun responded, generally sympathetically but, in keeping with the vision of the federal government held by most Americans in the nineteenth century, insisting that such protections were none of Washington’s business.

Unsatisfied, Smith decided that if the men running would do nothing, he would run himself. Using the existing church network, campaigners were sent out, state conventions were planned, and even a national convention was scheduled for July in Baltimore, the same city in which the other candidates—Henry Clay for the Whigs and James K. Polk for the Democrats—would be nominated.

With the help of a ghostwriter, Smith produced a platform, “General Smith’s Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States,” which was distributed widely. Among other things, he called for the gradual emancipation of slaves, a national bank, the elimination of prisons, and, anticipating the twentieth century expansion of government power, the use of federal authority to protect the constitutional rights of the people.

Smith also addressed the great issues of the day, supporting westward expansion and Texas annexation. It’s here that McBride gets his timeline mixed up a bit. He writes that Smith was writing his campaign platform at the same time Calhoun was negotiating the Texas annexation treaty. The treaty negotiations were largely finished by Secretary of State Abel Upshur before he died in an explosion aboard a Navy vessel on February 28. Smith read his platform in public on February 8. Calhoun did not become secretary of state until April 1.

But the timing confusion doesn’t alter the larger point, that Smith was engaging in a substantive way on the issues that voters cared about the most. His candidacy might have been mostly symbolic and entirely hopeless, but it was a real campaign.

Alas, Smith would not live to see the result in November. The mobs that he had implored state and federal officials to do something about would murder him in June, bringing his quixotic presidential campaign to an early end.

As an editor of the prophet’s papers, McBride is steeped in the primary sources and uses them to full effect without getting bogged down. He necessarily visits the campaigns of the other candidates, although a bit more rumination on the broader political events of 1844 would have added useful context to the story. The Philadelphia Bible Riots, a simultaneous instance of mob violence against a religious minority, highly relevant to the issue at hand, are barely mentioned.

McBride’s argument that Smith’s campaign provides an “indispensable lens” through which modern readers can “understand the persistence of religious inequality in American society” is thoroughly vetted and soundly defended. That makes Joseph Smith for President essential reading for anyone looking to understand the intersection of politics and religion in nineteenth-century America.

John Bicknell is the author of America 1844: Religious Fervor, Westward Expansion and the Presidential Election That Transformed the Nation and Lincoln’s Pathfinder: John C. Fremont and the Violent Election of 1856, co-editor of the 2012 edition of Politics in America, and senior editor of the 2016, 2018, 2020, and 2022 editions of The Almanac of American Politics.

Support The University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!