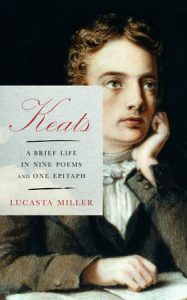

By Lucasta Miller.

Knopf, 2022.

Hardcover, 368 pages, $32.50.

Reviewed by Paul Krause.

John Keats wrote to his brother on October 14, 1818, “I think I shall be among the English Poets after my death.” Those prophetic words have come true, though when written in late 1818 the English literary establishment would have laughed at such a possibility. John Keats was not successful in his lifetime. While published by the radical pamphleteer Leigh Hunt, Keats fell outside the English literary mainstream which mocked his writings. Keats, as we know, died at the tender young age of 25 in Rome from tuberculosis. A few decades after his death, however, the apotheosis of Keats began, and he is now regarded as one of the greatest English Romantic poets and among my own personal favorites.

Why should one read another dead poet, a dead poet who also happens to be “a dead white European male?” Lucasta Miller, in her brilliant new book on Keats, writes, “To read him is to participate in an invisible web that has connected human beings over millennia via the literary imagination. Keats was inspired by earlier poets from Virgil to Shakespeare, and he himself went on to inspire creativity in others, from poets such as Oscar Wilde, Thomas Hardy, and W.B. Yeats to the science fiction novelist Dan Simmons.” To read is to enter the heavenly communion of artists past, present, and dare we say with Edmund Burke, those yet to be born.

Keats: A Brief Life in Nine Poems and One Epitaph is not your ordinary biography. Miller even admits that it is not really a biography as much as it is an attempt to uncover the genius that went into some of Keats’s poems over the course of his short life. But it still reads as a partial biography taking us through a chronological pilgrimage over that short but now eternal life.

Miller acknowledges that this book is “by a reader for readers.” Presumably, the reader of this book is meant to have some passing knowledge of Keats. Yet if one does not, one will certainly learn much of a man sometimes placed alongside the likes of Percy Shelley and Lord Byron. As readers, we encounter nine of the great anthologized poems Keats wrote, each with its own chapter, with our author taking us on a tour through what the poems reveal about Keats’s life as he wrote them.

Keats may be described as a poet’s poet. Or, more accurately, Keats’s posthumous apotheosis has given to posterity the notion of what a modern poet should be: young, restless, transgressive. Keats was not the first to embody these values that are now all but ubiquitous among poets—good or bad—but Keats and his fellow contemporaries, like Shelley and Byron, are all but synonymous with this idea of artistic and poetic genius.

Early nineteenth century England, and Europe, was a world in transformation. The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars waged for much of Keats’s young life. England was also in the throes of social change with the emergence of radical politics, the Industrial Revolution, and the emerging urban middle class to which Keats belonged. (Befitting Keatsian hagiography, those who perpetuated Keats’s metamorphosis from failed poet to poetic genius claimed him as an underclass “rags-to-riches” and also a respectable upper middle class poet pending their need). Europe was also open to travel in the post-Napoleonic settlement. Keats’s own life was one of geographic dislocation, mobility, and travel which influenced his own poetic imagination and style.

Keats got his beginning with Leigh Hunt, the radical pamphleteer and publisher of The Examiner which rankled the Tory establishment for its liberal politics and reinvention of the English language. It would not be correct to say Keats was a smashing success. He was no Wordsworth, no Coleridge, no Byron. These men of Romantic fame were famous in their day and celebrated as poetic geniuses too. Keats’s first collection of poetry was a flop, if sales and money-making is a metric to measure success. Keats’s early poetic beginnings, however, brought him into a network of new and emergent poets and editors who supported him despite the troubles and disappointment surrounding his poetry. This gave Keats the network to continuously publish his poems that would eventually be recognized later on as works of genius and inspiration.

What makes Keats such a central figure in the Romantic canon and pantheon is the posthumous reconstruction of Keats. His contemporary Charles Brown wrote an unpublished biography of his friend which was published in 1937 to much success and fanfare. In it, the construction “of a Keats supremely uninterested in anything beyond the moment of inspiration” stuck and has since become the cultural memory we have of Keats. Likewise the idea of the artist as an instant explosive genius has become normative.

But it was not Brown’s biography which gave to the world the Keats of contemporary renown and fame. That was already occurring decades after his death, primarily among the mid- and late Victorian aesthetes who reimagined Keats as “a disciple of pure beauty: apolitical, disembodied.” This is not true, as Miller points out. Throughout his poetry Keats is very much political and far from disembodied; his writings were “not just about escaping reality but embracing it.” Nevertheless, the Victorian aestheticization of Keats has also stuck, just like Brown’s Keats of in-the-moment inspirational genius.

The truncated Keats of hagiographic divinization, however, is not the reason we gravitate to his poetry. We love Keats because, as Miller points out as she guides us through Keats’s poetry and life, he simultaneously embraced poetry as a rest from our restless lives while not removing the nitty-gritty reality of the muck and mud world we live in. Life is messy and complicated. Love is messy and complicated. Genius is messy and complicated. And Keats’s poetry and own life is messy and complicated. We find ourselves, our own hearts and souls, in its aspirations and disappointments, in the poetry Keats bequeathed to the world.

Miller asserts that “Keats spent his poetic career worrying away at the challenge of how art should respond to the sordid, quotidian reality of individual human suffering, and whether it could assuage it.” When reading Keats, we see precisely that: beauty and suffering, hope and despair, resurrection and death. In suffering, there is life. In grief, there is love.

Keats’s life embodied suffering and grief, love and hope. That is, perhaps, one of the reasons for Keats’s remarkably relatable poetry even if set in mythic lands with mythic characters. Far from make-believe, whether Isabella or Madeline and Porphyro, the characters and the human hearts of love they have are instantly recognizable. In them we see ourselves. And, through Miller’s brilliant writing, we also see Keats in them.

Lucasta Miller reminds us that poetic genius is not just instantaneous moments of rapturous creativity. In fact, she demythologizes the mythologizers. Some of the hagiographic cultural memory of Keats was made up or misremembered by those who began resurrecting Keats as a failed poet to eternal prophet and genius. This does not tear down Keats’s stature and posthumous legacy. In many ways, it solidifies it. Keats’s troubles and his revisions are inspirational to aspiring writers—first drafts need not be perfect, and lines that are now remembered by so many, like “A thing of beauty is a joy forever,” were not the first drafts authored by Keats but the product of revision and inquiry to friends about their quality.

Keats: A Brief Life in Nine Poems and One Epitaph is a remarkable achievement by an exceptional literary critic and scholar. Keats comes to life through Miller’s writing, and we come to love Keats even more than we had before reading. Undoubtedly, Keats would be joyful of the beauty that Miller has given the world in this new life of one of England’s greatest poets.

Paul Krause is editor-in-chief of VoegelinView and the author of The Odyssey of Love: A Christian Guide to the Great Books (Wipf and Stock, 2021).

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!