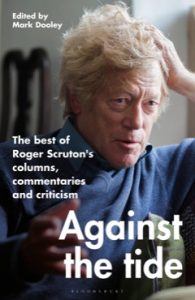

Edited by Mark Dooley.

Bloomsbury Continuum, 2022.

Hardcover, 256 pages, $28.

Reviewed by John G. Grove

How should the conservative respond to a time in which so much seems to be lost? Desperation seems to be the response of many. “Conservatism is not enough,” we are often told: “there is nothing left to conserve.” The constitutional order that conservatism has long sought to preserve and perfect has brought only cultural decadence. We must abandon it in favor of bold new political projects. Every election presents the specter of civilizational collapse. Is such pessimism warranted?

Anyone who has read The Uses of Pessimism will know that Roger Scruton was a very different kind of pessimist. In that book, he outlined what might be thought of as an optimism rooted in pessimism: We ought to be broadly pessimistic about the ability of human beings to recreate the world according to their sense of what it ought to be. Dreams of future utopias or past golden ages, therefore, are usually distortions. In this world, we will have troubles. Offenses must come. Injustices will always be with us.

But this kind of pessimism paradoxically leads us to fields of hopeful labor by turning our eyes away from the lofty and unattainable dreams of the visionary to the world right in front of us, which always presents us with opportunities to do good and resist evil. So Scruton ends that book on pessimism with a hopeful call to “look with irony and detachment on our actual condition, and to study how to live at peace with what we find.”

That same attitude is on full display in Against the Tide, a new collection of Scruton’s shorter essays and columns, edited by his literary executor, Mark Dooley. As the title suggests, these short broadsides show Scruton doing battle with the prevailing forces at work in our corrupt age.

The opening lines of the 1994 column, “The Conservative Conscience,” could be pulled from the pages of any conservative media outlet today: “We live in troubling times”; the West is “adrift without leadership.” “Social decay”—including “crime,” “pornography,” confusions about sex and gender, and diminishing religious faith—is all around us.

But the message is not one of despair, for Scruton does not make the mistake of believing that aggregate social trends—as alarming and important as they are—control us or prevent us from speaking truth, doing good, or appreciating beauty. “The choice lies before us, as it has lain before every human being in history, to live well or badly, to be virtuous or vicious, to love or to hate. And this is an individual choice, which depends on cultural conditions only obliquely, and which no other person can make in our stead.”

What’s more, living in “this time of decay” gives us rare opportunities. We owls at the dusk remain heirs of Western civilization and are able to understand its virtues perhaps better than any other generation, for we have seen the consequences of abandoning its traditions. So as much as any other men in history, we are well positioned to speak the truth, live well, and teach those who come after us about the great value of their inheritance.

Politics was important for Scruton, if for no other reason than the old Platonic one that it is better to rule than to be ruled by fools (or frauds, or firebrands). But he did not look to it to save Western civilization. That cannot come from politicians, whose job “is not to create a society but rather to represent it.” If it is to be saved, it will be by “the educator, the priest, and the ordinary citizen whose public spirit is aroused on behalf of his neighbours”—by regular people who love the place where they are and wish to improve it.

Throughout the collection, Scruton identifies, dissects, and thrashes cultural and political forces, including socialism, individualism, feminism, identitariansim, scientism, atheism, utilitarianism, and just plain academic “gobbledegook.” He does this not to show that all is lost; not to rally the troops to vote in the next election; not to map out some grand project that will immediately turn the tables. Rather, he believed we must understand the diseases of the current moment so that we can seek and speak the truth, live well in our time and place, and do what we can to repair our social fabric.

When surveying our social and cultural landscape, it would not at all be surprising to hear that the people of the modern Western world lack “purpose.” Any number of self-help gurus might advise their lost readers to “find purpose” and order their lives according to clear goals.

There is something to this, of course—“finding purpose” might just be shorthand for doing something more valuable than video games or recreational drugs. But Scruton’s take on “purpose” is the opposite: it is the very drive to make everything in life “purposeful” that has caused us to lose sight of those things that are valuable for their own sake, things like wisdom, faith, and beauty.

Education is the most potent example. In “The Virtue of Irrelevance,” Scruton explains how an education that is constantly stressing its relevance keeps students’ eyes squarely focused on themselves, thus accomplishing an effect that is the very opposite of what education ought to do.

This tendency manifests itself in two ways: an emphasis on career readiness—STEM education, “applied mathematics,” and the like—and social justice training. The former keeps students from studying anything of moral value. The latter filters all the great sources of moral formation through the unquestioned assumptions of leftist ideology. History, literature, music, philosophy, and anything else that threatens to make students think more deeply or critically about their political and moral views, are all made into simple tools of social activism. Students must study with purpose, after all. They must aim to change the world.

This purposive education encourages us to “see through” the things that have traditionally been understood as intrinsically valuable. We can build a more “inclusive” world if we give up on the idea that there is any certain truth to be sought out: “The person with certainties is the excluder, the one who disrespects the right we all have to form our own ‘opinions’ about what matters.” Truth-seekers are offensive, for they hold out the possibility that certain things—books, music, habits—are more praiseworthy than others. Such an opinion contributes to the only thing that is, apparently, truly blameworthy: hierarchy.

Like truth, beauty is also something that our purposive age would have us see through. We have destroyed more and more beautiful buildings for “concrete slabs” that can accommodate more parking spaces, office cubicles, or commercial space. Art has shifted from a pursuit of beauty to a tool of power designed to tear down received truths.

And of course, faith is not exempt. Scruton takes on the “New Atheists” who try to “see through” religious belief by reducing all human experience to flesh and blood. The “great scientistic illusion” always has a further explanation for our thoughts, emotions, and actions, meaning we are no longer moral actors, but mere pieces of matter robbed of “morality, commitment, and trust.” If religion is to be “purposive,” then, it must take on “large-scale worldly enterprises” to “fight oppression … racism … or nuclear weapons.” Saving souls just does not seem to produce results.

These ideologies, however, are always self-contradictory and often self-defeating: An education that tries to abolish certainties can do so only by creating its own set of unquestioned certainties. The ugly concrete slabs, Scruton notes, often sit empty after only a few years, because no one values them. Though he does not explicitly point it out, churches that put activism ahead of divine gifts often have no one to warm the pews.

Here we see how Scruton’s “pessimism” could never be confused with hopelessness. He did not underrate the dangers that these modern ideologies pose, but he also recognized that they all contain fatal flaws, for they fail to satisfy our deeper human needs and longings. Normal people continue to recognize instinctively the value of the family; we all have a continuing need for the sacred; “[o]rdinary people hunger for beauty as they have always hungered.”

So Scruton rarely seems worried in these pages that the pervasive modern ideologies will win permanent victories that stamp out entirely the things conservatives value. On the contrary, he saw how, even in the most repressive of recent regimes, where “truth and trust were crimes,” flames were kept burning on underground altars. Indeed, they often burned brighter than when times were good. We may not be able to direct the arc of history, but if we “take comfort in handing on knowledge to one person,” it will help us to endure the scorn of a world that has turned its back on wisdom, faith, and beauty.

Against the Tide offers glimpses into Scruton’s personal life by the inclusion of a few diary entries, where his hopefulness in the face of troubles carries over. During the last year of his life, even as he grappled with rapidly progressing cancer, he was the target of vicious calumnies against his character that resulted in his temporary removal from the Building Better, Building Beautiful commission. In this dark personal period, Scruton took strength from things that are of permanent value, most clearly from art and friendship. “Coming close to death you begin to know what life means, and what it means is gratitude.”

Those are the last words of the collection. Conservatism, Scruton reminds us, is “about loss: it survives and flourishes because people are in the habit of mourning their losses, and resolving to safeguard against them.” That habit also entails gratitude—for the things that are worth mourning and for the things we still have to conserve.

John G. Grove is the managing editor of Law & Liberty.

Support The University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!