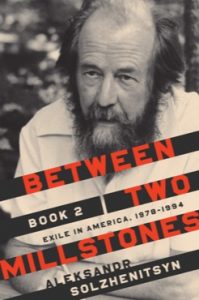

by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.

University of Notre Dame Press, 2020.

Hardcover, 584 pages, $39.

Reviewed by Jeremy Kee

The world as a whole, and the United States in particular, is changing more quickly and completely than the individual human mind is capable of fully processing and integrating. The term for this phenomenon is “Liquid Modernity,” coined by the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman. One never knows, for example, when a mob claiming to protest injustice will ransack a metropolitan zip code, or the followers of a reality-distanced political cult will launch an insurrection against the U.S. Congress. Under the auspices of liquid modernity, one knows not what existential crises may yet unfold between arriving home from work and the evening news.

Over the course of the last century, there have been a few individuals who have taken note of the quickening pace of the modern world and offered warnings which, per the tradition of the long history of dire warnings, were roundly dismissed, mocked, and antagonized. To take one example, there is certainly ample criticism of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s Harvard Address (officially titled A World Split Apart), in which he pointed out the spiritual weaknesses of the West while highlighting unsettling similarities between our capitalist materialism and its Communist counterpart in the USSR. Conversely, it’s much more difficult to find fair critiques of that same address, and even then, they are often riddled with skepticism and qualified comments.

As is so often the case, it is only long after the fact, indeed most often after the deaths of such figures, that their warnings take root—long after they should have, well within the temporal category of “Too little, too late.” The idea of the city gate, after all, was to keep the invaders out; closing it only after invasion merely hampers one’s own escape.

It is with these thoughts in mind that we turn to the recently published second volume of Solzhenitsyn’s literary autobiography, Between Two Millstones, Book 2, published by the University of Notre Dame Press. Readers of Book 1 will recall the remarkable emphasis Solzhenitsyn placed on securing his notes, papers, personal library, and other intellectual resources. To read Book 2, particularly if one has already read Book 1, is to experience a master course in what it means to be a “Russian writer”—not just an occupation, but indeed a divinely appointed vocation. The second volume picks up where the first ends, just after the Harvard Address. Rather than offering immediate intellectual counterpunches—which come in due course—Solzhenitsyn instead writes about the peace and tranquility found on the Solzhenitsyn homestead in Vermont. Much of the first chapter is spent painting a picture of a Russian family adjusting to American life. Here, the reader sees Solzhenitsyn in his most neutral state; he is not Solzhenitsyn (as he regularly referred to himself), nor is he Solzhenitsyn the Nobel Laurate, Gulag survivor, and acclaimed Russian writer. Rather, he is merely Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn, Russian émigré, husband, and father of three.

Solzhenitsyn offers remarkably pacific insights into the daily life and habits of a serious intellectual while also taking to task his many interlocutors. He makes known within the opening pages (and repeatedly thereafter) that he finds Americans to be intellectually lazy. To wit, when talking about the reading public both Russian and Western,

“But the Western public these days has, it seems, totally lost the habit of reflecting on books—though perhaps they do on journalistic articles—and Western writers themselves for the most part do not lay claim to the power of persuasion. Current literature in the West titillates either an intellectual or popular readership: it is degraded to the level of entertainment and paradox, no longer of a standard to mold minds and characters.”

It is this same frank and insightful observation that made him an ill-remembered figure; not because he was wrong, but because in his honesty he was not always pleasant. Though, in his defense, “The truth is seldom pleasant; it is almost invariably bitter.”

The author’s chief concern is, as always, how little time he has to work on his manuscripts for The Red Wheel between controversies. In fact, one is hard pressed to read more than a full page without the author making some ornery remark about having been disrupted by myriad distractions. It is also a valuable insight into the unchanging nature of the modern media.

The manner in which Solzhenitsyn regularly experienced attempted character assassinations and betrayals, the games played by many publications still enjoying the greatest journalistic prestige in our own day, the lies, the half-truths, the slander, fabrications, assumptions, and misinterpretations (willful or otherwise)—it is illuminating, providing a reliable historical account of media malpractice. One may criticize the media in our own day and be comfortably justified in doing so, but it is important to note that a corrupt media is not an evolution, but rather a revolution, a cycle that goes around and around making all the same noises at all the same points in time.

To this end, it is commendable that Solzhenitsyn was able to weather such tempests or, perhaps stated more accurately, why he chose to wander into such storms after having survived the Gulag, escaped the Soviet Union, and opened the eyes of the world to the reality of Soviet and Communist brutality. In a sense, he offered himself as a literary martyr; a liar would have surrendered and found a less painful life. No one ever died for a lie, and yet Solzhenitsyn was the subject of assassination attempts both figural and literal. One would think that a person so despised by the Soviet Union for the crime of writing would be worth taking quite seriously. Solzhenitsyn was, until that mirror was turned on the Western media.

Perhaps the lengthiest but most important single episode recounted in Book 2 is Solzhenitsyn’s account of working with his biographer, Michael Scammel. For anyone familiar with this affair, reading this autobiographical account offers a fascinating first-hand view into the complicated professional relationship between the two men. For those who are unfamiliar, it is an edge-of-your-seat intellectual thriller, a rollercoaster of literary intrigue. Not one to mince words, Solzhenitsyn presents his opinion on the man in unvarnished splendor. While it seems that Solzhenitsyn was never terribly fond of Scammel, painting a figure of a man desperate to be admired—a theme, as we shall see, that runs throughout the whole tawdry affair—he was nonetheless kind and accommodating to the biographer’s requests. Perhaps the most telling description Solzhenitsyn offers of Scammel is calling him “well intentioned” in his efforts.

Things soon began to unravel, as Scammel’s well-intentioned diligence began to interfere with Solzhenitsyn’s literary efforts. Anyone who has ever brought home a puppy will understand their relationship. Solzhenitsyn foreshadows the ugly turn to come, calling an item of their correspondence “a devious reply,” while at another point writing, “And I believed him [Scammel]. How wrong I was. Why stand in the way of such sincere intentions?” The reader feels Solzhenitsyn’s frustration over Scammel’s “umpteenth query” before making note that he had begun to receive “dozens and dozens” of follow-up queries (after the umpteenth). After several attempts by Scammel to invite himself to the Solzhenitsyn property, the Russian writes,

“We agreed that he would come in June 1977. With a firm proviso: we will answer all questions freely, as many as you can fit in, but that’s the end of it. Don’t come back for any more.”

To no one’s surprise, this would not be “the end of it.” In fact, the biographer would make several more visits, all at his own insistence. This tedious relationship persisted until 1981, when communication with Scammel simply ceased. After more than a half-decade of well-intentioned annoyance, Scammel had finally shut up. In fact, he would send not so much as a note again until August of 1984, when he sent a notification that the biography was going to press. Suffice it to say, publication of the biography of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn—titled simply Solzhenitsyn—represented the opening of a new front in the battle between the author and a press uninterested in the accurate conveyance of facts or truth.

To read of the Scammel ordeal is to read a summary of Solzhenitsyn’s tempestuous relationship with the West; a writer whose insights into the darkest corners of the soul served an arguably greater role in the fight against Soviet socialism than any individual before or after; whose same insight would then be used against him when his gift of seeing through the veil of the political to the spiritual began shaking the halls of power. Solzhenitsyn makes quite clear that he was at peace with what he hoped would be a gradual fade into relative obscurity. He had seen enough of war and was disinterested in much else beyond finishing his Red Wheel and living a life of peace.

It is telling that after the Soviet Union, the man’s greatest foe was Western media. And yet despite the myriad distractions he remained singularly focused: not on defending his honor in the public square, nor serving as a master of puppets, but in telling the story of the Russian soul under the oppressive thumb of Soviet socialism.

There are countless takeaways from Book 2 of Between Two Millstones, as well as its predecessor. The set forms the intellectual autobiography of one of the truly great men of the twentieth century, a man whose absence in history would have resulted in much darker and more dire outcomes for all people of this good earth. As with the prophets of old, he was mocked and derided in his own time, and as with those prophets, the passage of time provides the greatest testimony to his importance. It is imperative to study men like Solzhenitsyn, to learn the lessons of their lives and life’s work lest we doom ourselves to tread those same lonely vales. We must remember them, that we may stoke the smoldering fires of our human potential.

Jeremy Kee is a licensed professional counselor and writer living in Dallas, Texas.

Support The University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!