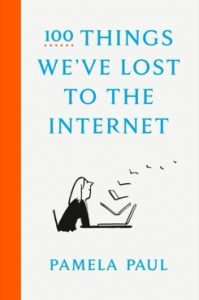

By Pamela Paul.

Crown, 2021.

Hardcover, 288 pages, $27.

Reviewed by Auguste Meyrat

Few inventions in recent memory have been more disruptive and influential than the internet. Only a few decades ago, the great whole of humanity lived in a physical space that bound their vision and control of reality. People simply did their best to react appropriately, make the most of their experiences, and accept the limits of their perception and knowledge.

By contrast, most people today live in a virtual space largely within their control. They can decide what to see, hear, and think about for the greater part of their day. Online, people themselves can determine how they interact with the world and what they want to show to others. In this way, the internet is an innovation that is both empowering and enabling.

To comprehensively catalog the many changes that the internet has introduced to modern life would be too much for any one person to do in one book. The effort would require many writers writing many volumes to even come close to sketching a complete picture of what the internet has done to society.

In her newest book 100 Things We’ve Lost to the Internet, Pamela Paul does the next best thing and gives her personal analysis of the negative changes that have accompanied the internet. As suggested in the title, the book features a hundred essays that each focus on one particular aspect that has been lost to people today, including large and profound things like psychological closure or small and trivial things like card catalogs.

Although Paul takes on a weighty subject that is ripe for insightful reflections on the human condition, most of her chapters tend to sidestep this as she strives to charm the reader. In this endeavor, she is largely successful. She is humorous without being mean-spirited or overly curmudgeonly: “What was this paperwork of which you speak, asks the Gen Z worker. And this ‘pushing papers’ people once supposedly engaged in.” The illustrations by Nishant Choksi interspersed throughout the book also help.

Of the hundred things that the internet took away, the majority of them fall into three categories: social interaction, living in the moment, and having a personal record. In no particular order, Paul will periodically revisit these themes and gradually put together a picture of today’s brave new world in which the internet has inserted itself into everything.

Whereas social interaction used to be more spontaneous, reactive, and authentic, Paul shows how the internet has eliminated these qualities, resulting in sterile relationships and missed opportunities. No longer do people encounter strangers on the airplane and have long conversations with them, nor do romantic couples meet one another by chance and have a story to tell their children. Rather, everything is planned, most conversations are filtered through screens, and the public is privy to everyone’s personal life.

A similar phenomenon has happened even when people are alone. Those moments of introspection or experiencing something first-hand are now interrupted by the desire to post it online for the world. As Paul ruefully observes, “We disrupt ourselves—all the time, even for one quick second, a momentary glance at the screen.” There is never a dull or quiet moment. This may make life more exciting and engaging, but it also makes people more superficial and unoriginal.

To make matters worse, everything is recorded. Every messy scene, stupid thought, unflattering image lives forever in cyberspace. Not only does this drain every moment of urgency and reality, it also prevents people from moving on with their lives. Nothing ever comes to an end and a whole lifetime is flattened to an ongoing present that most people are not even present for.

When Paul is not hitting on these ideas, she indulges in Gen X nostalgia—a lot of it. Remember the landline phone in the kitchen? That nice librarian who introduced you to your favorite book series? Playing trivia with the names of actors and the year a certain movie came out? Passing notes in class? Carefully organizing your CD collection, or getting bad-quality photos developed, or reading TV Guide? Did you want to remember these things?

This nostalgia overload is the book’s biggest weakness. Perhaps it is the challenge of coming up with one hundred things to write about, but after about fifty things, Paul’s argument and style can often frustrate a reader hoping to go further with an idea and consider its implications.

For example, she begins her book with some interesting points about boredom only to move on to her next chapter about the current habit of not using periods in informal communication. True, this shows the book’s wide range of subjects along with Paul’s characteristic levity, but it also renders her general logic incoherent. Whether it is finding a random item at a flea market or cultivating empathy, it is all treated equally and given the same amount of attention.

It also does not help that Paul seems to lead a rather privileged life that results in her exclusively seeing the internet’s drawbacks. The reader gets the feeling that Paul is mostly upset at the internet because she cannot look smart and cool anymore. She cannot show off her good taste, talk about her interesting encounters with others, or showcase her originality. While her white-collar workplace, bourgeois rituals, and trips abroad will resonate with readers who share the same social class, they can become cloyingly obnoxious to those who do not.

For people who grew up outside New York City, received average educations, and only had access to mainstream media, the internet has been a great boon. It has allowed people of all backgrounds to hear different voices, do their own research, and make their own contributions to public discourse. No longer are people in the flyover states or peripheral countries condemned to a provincial lifestyle and mindset. They can learn about the world and have choices about what they think and believe.

One would hope that Paul includes “narrow-mindedness” or “irrelevance” on her list of things that were lost because of the internet. After all, she is not opposed to crediting the internet for helping people find others like them and not having the “awful and oppressive feeling” of being the only “gender-fluid teenager” or “young widow” in the world. However, the great opportunities of learning and speech brought about by the internet seem to elude her entirely.

Despite these drawbacks, 100 Things We’ve Lost to the Internet is still a fun read overall. Even in its relatively limited scope, it goes a long way in showing the way life has changed for many people, often leaving them spiritually and emotionally impoverished.

Fortunately, the story does not end there. Whatever new invention enters the scene, it will always be up to the individual to learn how to best manage this development. As with any disruptive technology, be it the printing press, the telegraph, or the television, the challenge for people will always be to strengthen their connection to internal and external realities. And this is still possible today, if readers heed the advice of Pamela Paul and finally look away from their screens from time to time and recover what they have lost.

Auguste Meyrat is an English teacher in the Dallas area. He holds an MA in Humanities and an MEd in Educational Leadership. He is the senior editor of The Everyman and has written essays for The Federalist, American Greatness, Crisis Magazine, and The Imaginative Conservative as well as the Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture.

Support The University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!