by Fredrik Logevall.

Random House, 2020.

Hardcover, 792 pages, $40.

Reviewed by Jason K. Duncan

Last year, 2020, marked the sixtieth anniversary of John F. Kennedy’s election as president in 1960. Given the heated nature of last year’s presidential campaign, few Americans were inclined to look to past elections for guidance or comfort. Some historically minded commentators did look back, ominously, to 1860. As for the 1960 presidential contest a century later between Kennedy and Richard Nixon, it was largely marked by a general consensus on the rightness and necessity of waging the Cold War, with Kennedy claiming that the United States had become complacent and sluggish in doing so. Even in his opening statement in the first televised debate with Nixon, the focus of which was to be domestic affairs, Kennedy insisted that the main challenge facing the United States in 1960 was “our struggle with Mr. Khrushchev for survival.”

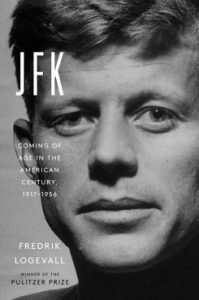

In what has been heralded as the first volume of perhaps the defining biography of John F. Kennedy, Fredrik Logevall’s JFK: Coming of Age in the American Century, 1917–1956, emphasizes how Kennedy’s life was shaped by the rise of the United States as a global power. Logevall comes to his study of Kennedy after publishing widely on U.S. foreign policy and international affairs. The native of Sweden is best known for Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America’s Vietnam (2012), on the French defeat in 1954 and the origins of American involvement in the Vietnam War. For that book he was awarded a Pulitzer Prize.

Intense political polarization made domestic matters the overwhelming focus of the presidential campaign of 2020, and foreign affairs were often reduced to allegations that the major political parties lean toward either Russia (the Republicans) or China (the Democrats). That may be why Logevall’s JFK has done better with reviewers than it has fared on the best-seller lists. In the always crowded field of presidential biography and autobiography, it has been outsold by the first volume of Barack Obama’s memoirs, and by various books attacking and defending Donald Trump. But the merits of this study will surely gain it a wider reading audience in due time. An historian at Harvard and a researcher of great range and depth, Logevall brings readers through the first four decades of Kennedy’s life with remarkable energy, patience, and skill. This biography is a model of the genre.

The Irish-American context is an inescapable part of any Kennedy story, and Logevall gives it its due. In rich detail he describes how Kennedy’s ancestors left Ireland in desperation in the middle of the nineteenth century to escape famine and starvation, only to find an uneasy refuge as immigrants in Yankee Boston. The Kennedys, Fitzgeralds, and others avoided the worst of life in Irish Boston and made opportunities for themselves through hard work, education, and starting small businesses, and eventually, politics. Even before the dawn of the twentieth century, one of Joseph P. Kennedy’s uncles had graduated from the Harvard Medical School.

The marriage of his parents was a union of two politically influential Boston families, the Kennedys and the Fitzgeralds. John Fitzgerald Kennedy was born in May of 1917, the month after Woodrow Wilson persuaded the United States Congress to declare war on Imperial Germany. Young Jack Kennedy received mixed messages from his parents about fundamental matters such as the Catholic faith, family, and marriage—which Logevall explains as well as he (or anyone else looking in from the outside) can. JFK took after his father, for whom he had great respect and affection, in his pursuit of women for short-term relationships. While he credits Kennedy for not slavishly following his father’s thinking on politics, he faults him for this personal behavior. JFK continued his dalliances after his marriage to Jacqueline Bouvier in 1953, whom Logevall captures well. Logevall has said that Kennedy’s conduct toward women became more “predatory” over time, a grim warning of what readers will encounter in volume two.

Making his way through a series of prestigious private institutions on the East Coast, culminating in his graduation from Harvard in 1940, Kennedy battled poor health and compiled an often mediocre academic record. Logevall credits JFK with great courage in battling a long series of his childhood illnesses—more than once he was at death’s door—and that he rarely gave in to self-pity, something his parents discouraged in their children. He stresses Kennedy’s general likeability and ability to make friends (usually on his own terms) and an independence of mind, one encouraged by both parents. He does point out that some of Kennedy’s prep school classmates found him “glib and cavalier,” and a few of his old friends found, to their disappointment, a new self-centeredness emerging as Kennedy began his political career, becoming more distant from them, while maintaining close ties with “toadies” who would never challenge him.

The John F. Kennedy who would become president is more recognizable during his final years at Harvard. Logevall opens JFK with Kennedy in 1939 Berlin, a witness to the Nazi Empire as it prepared to unleash war on Europe. It was foreign affairs that captured his imagination. Kennedy’s political idol was British conservative Winston Churchill, whose steadfast leadership in urging his countrymen to face the threat from Hitler captured his imagination, and not the American liberal Franklin Roosevelt. With the help of his father’s connections, Kennedy published a revised version of his senior thesis as Why England Slept, paying tribute to Churchill’s While England Slept. Using London as a base while his father served as U.S. Ambassador to Britain, he traveled extensively in Europe and the Middle East, his curiosity driving him to seek out leaders and people in the know about the political situation in their countries and their views on the international situation.

And then came World War II. Enlisting before Pearl Harbor, Kennedy parlayed his family’s connections to get into the Navy and then secure a front line position, despite physical drawbacks that would have allowed him to serve from a desk. In the South Pacific, he piloted his new and not-so-well-designed vessel, the P.T. 109, into harm’s way. It was split in two in the darkness of night by a Japanese destroyer, resulting in the death of two members of Kennedy’s crew. In some of the most riveting pages of the book, Logevall narrates the leadership and courage Kennedy displayed in the aftermath of the collision. Kennedy’s experience in the Navy convinced him of the necessity for greater American engagement in the world, even as it made him skeptical of war itself and of those higher up on the military chain of command.

Some of the publicity promoting JFK touts it as the first biography to dismantle the popular image of young Jack Kennedy as a callow and feckless playboy, pushed forward against his will into politics by a domineering father. In fact, no serious students of John F. Kennedy’s formative years have put forward that argument. Logevall though does further establish that Kennedy had his own interests and ambitions regarding public life. The idea of launching a campaign for an open seat in the Congress in 1946, for example, was his, not his father’s. Joe preferred that his oldest surviving son become a candidate for Lt. Governor of Massachusetts. In a largely working class Congressional district in the Boston area, Kennedy, who found to his surprise that its voters were more interested in matters of economic security than they were about the emerging Cold War, got a head start on his rivals for the Democratic nomination, outworking them in part because he did not have a day job, and with his father’s money he vastly outspent them. Along the way JFK brushed aside charges that he was a carpetbagger (true in part) and a rich man’s son (entirely true, but he was also a veteran who had seen action and the son of a Gold Star mother). He quickly developed, after shaking off some early jitters, an unaffected campaign style that most voters found to their liking.

Becoming a member of the House in 1947, the crucial year in the making of the Cold War, Kennedy by and large supported the policies of the Truman administration. He was critical of former vice-president Henry Wallace, who praised the Soviet Union for its economic policies and urged the United States to continue the wartime alliance between the two nations. Kennedy, the novice politician, took Wallace to task for his naiveté, and urged a tough line against Moscow. A seeker of the “pragmatic middle ground” in politics, Kennedy did not call for a return to pre-war isolationism, as his father desired, but as a veteran “tempered by war” as he described himself in his inaugural address fifteen years later, he joined with those calling for unprecedented American leadership in the world.

Kennedy proved to be an indifferent junior member of the House, bored with the workings of the institution and not willing to put in the decades of service needed to climb the leadership ladder. Instead, he challenged the popular incumbent Republican Senator Henry Cabot Lodge for his seat in the Senate. Among the keys to Kennedy’s victory in what was a good year for Republicans in Massachusetts was his strong showing in traditionally Republican small town and rural areas. With the historian’s eye for detail, Logevall notes that Kennedy, while losing those communities to Lodge, ran ahead there of other Democrats. He cut his losses by regularly visiting communities that rarely saw statewide Democratic candidates.

In the Senate, Kennedy did not make a reputation for himself as a master legislator or a leader of his party. He was away recovering from back surgery when the Senate took up the matter of Joseph McCarthy, who had connections with Joe and Bobby Kennedy. Logevall has drawn criticism, some of which he has acknowledged, post-publication, as legitimate, for not indicting Kennedy more vigorously regarding McCarthy. Yet Kennedy would have almost certainly joined with all of his Democratic colleagues in censuring him, and as Jackie Kennedy said of her husband, “he was never one to run in a pack against [someone].” Kennedy’s independence of mind that Logevall and other biographers have praised was on display in the McCarthy episode as well.

Logevall also takes a measured stance on the other major controversy of Kennedy’s years in the Senate, surrounding the true authorship of his Pulitzer Prize–winning Profiles in Courage. Logevall has described it as a “centrist manifesto,” in which Kennedy praised Senators in the past who chose the national interest, as they understood it, over the demands of party or region. It is the rare politician who praises other politicians, but Kennedy was no populist, either of the genuine or the manufactured type.

Fredrik Logevall is not interested in resurrecting the mythology that grew up around John F. Kennedy after his death, but neither is he a grim iconoclast, the kind of which the world saw many in 2020. His humanist portrayal of Kennedy, combined with his formidable skills as an historian and biographer, makes this a valuable book. It mattered enormously who was President of the United States at the height of the Cold War, and by what influences the character and mind of such leaders had been shaped. Those desiring to know John F. Kennedy by more than the totality of his sins should read JFK, especially in a time of deep and worsening polarization in our country. There are lessons to be learned from the formative years and experiences of this flawed and important American leader.

Jason K. Duncan teaches in the department of history at Aquinas College, Grand Rapids, Michigan, and is the author of John F. Kennedy: The Spirit of Cold War Liberalism (Routledge, 2014).

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!