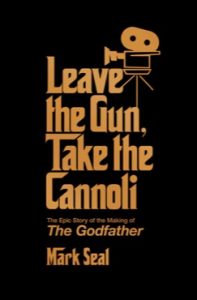

By Mark Seal.

Gallery Books, 2021.

Hardback, 448 pages, $29.

Reviewed by Paul Krause

I believe in the Godfather. Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather is, possibly, my favorite film. I say possibly because, although something of a self-confessed cinephile, deciding one’s definitive favorite film can be subject to mood swings that would make Sonny Corleone look tame by comparison. But on most days, The Godfather probably is my favorite film—assuming Part II is also attached to the first so both films embody what Mario Puzo wrote. There is so much depth, richness, and complexity to the tragic, romantic, and penetrating deconstruction of the world of the mafia that runs across the screen for three hours in that 1972 masterpiece that it is hard not to fall in love with it.

The Godfather is an epic. And Mark Seal has written an epic book detailing the highs and lows, struggles and triumphs, in the making of the Academy Award–winning film that catapulted Coppola’s career as one of Hollywood’s finest filmmakers and metamorphosized a broke overweight Italian American pulp magazine writer, Mario Puzo, to stardom. As the title of Seal’s book promises, and as the book painstakingly reveals, the making of the film was itself an epic in every sense. “The best picture ever made,” in the words of producer Robert Evans, was almost an entirely different film than what we thankfully received.

Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli opens with the grisly murder of a bootlegging baker from Toronto that would once again bring the mob into public light and government scrutiny. Then enters Joseph Valachi, the infamous mob soldier turned FBI informant that rekindled the drama of the Kefauver Committee that served as inspiration for scenes in The Godfather II. America in the 1950s and 1960s was gripped by the rise of television and media headlines relating to organized crime. And a failed middle-aged writer, drowning in debt and back taxes, somehow managed to pick himself out of the gutter and write the mafia novel that became the masterful work of art he always dreamed of creating but did not think this novel—The Godfather—would achieve.

Mark Seal writes that what made the Valachi testimony sensational was that it was about a story, a story of “mythic proportion,” a “story that encompassed the intertwined elements of family and brutality, of loyalty and betrayal, of fathers and sons, of immigration and the American Dream … its raw and epic power, would seemingly require a storyteller of immense talents—a modern day Shakespeare, a Homer, or a Virgil.” No one would have thought Mario Puzo would be that writer. Seal does a great job providing a concise biographical sketch of Puzo, from his childhood poverty to service in World War II to his unstable work and failed writing aspirations while drowning in gambling debt to his big break drawing on the mafioso legacy of the 1950s and 1960s in composing his novel that became an instant bestseller.

But the story of the making of The Godfather was, itself, an epic journey with twists and turns that would make Odysseus blush. The story about the making of The Godfather needed a great writer as well, and Seal manages to be that epicist, writing about an journey with a myriad of characters: men and women, young and old, charismatic and dull, poor and rich, Hollywood stars and acting unknowns, all assembled to create the greatest film in Hollywood’s history. Through Seal’s storytelling we crisscross a world of characters as lively as those portrayed in Mario Puzo’s book and brought to life in Francis Ford Coppola’s film.

Francis Ford Coppola was not the first choice to direct the famous mobster movie. Sergio Leone, who had risen to prominence from his spaghetti-western films, was Paramount’s first choice. Peter Bogdanovich was also considered ahead of Coppola.

While Seal glosses over these facts, he nevertheless highlights the tension at Paramount (itself struggling at the time) over who should be the director with other prominent names like Sidney Furie and Sam Peckinpah lobbying for the job while Coppola was defiantly disinterested despite his debt and impending bankruptcy. Eventually, the broke and burly aspiring artist turned filmmaker accepted the job—mostly because George Lucas pressured him due to their dire financial situation. The commercialism that had driven Coppola and his merry band of rebel artists out of Los Angeles for San Francisco paradoxically forced his hand into accepting the job because of the financial troubles that plagued them.

It is hard to imagine the film without Coppola. His name is stamped onto its eternity as much as actors like Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, James Caan, Robert Duvall, and Diane Keaton are. Seal argues that he was the perfect man for the job. His birth, life, and trajectory all seemed to position him for directing the most famous mafia film in history. Seal’s storytelling of Coppola on set and the battles he endured as a young director, especially with producer Robert Evans, add to the majesty of The Godfather as we realize how the film we all love was almost not to be.

In odd ways, Coppola and Puzo—the two men so essential to the creation of The Godfather—were the most unlikely of heroes to create such a masterpiece of art. It is ironic how two broke and burly men ended up as the driving forces of a work that both men thought was not art but a sellout for money. In this part of the book Seal does a magnificent job describing the artistic aspirations of both men, how both felt The Godfather was not high art, and how despite this they ended up making a work that has stood the test of time.

Throughout the book we catch glimpses and hear echoes of the film through Puzo’s life, Coppola’s directing imagination, the dinners, conversations, and backroom wheeling and dealing in the formation and making of The Godfather. The film is not only remembered for dialogue but also for its imagery—the grand aesthetic that radiates across the screen. Even when detailing how a washed-up Marlon Brando secured the role of Don Corleone, Seal’s writing transports us to the infamous opening scene between the Godfather and Bonasera. Describing the pivotal scenes, Seal’s writing is packed with perfect descriptions of what roared across the movie screen in 1972 to captivate the world and continues to do so fifty years later.

In Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli we are privileged to take a journey into the depths of the hell that was the making of The Godfather. But at the end of this journey, like Dante with Virgil in The Inferno, we come out the other side and witness the film’s transfiguration into “the best picture ever made.” For anyone who is a lover of the film, reading Seal’s fantastic book revives the images that have endeared five decades of film watchers.

This year, 2022, marks the fiftieth anniversary of The Godfather, the cinematic experience that captivated the world and revitalized the gangster genre and helped birth the Second Golden Age of Hollywood. Anyone who is going to reacquaint themselves with the 1972 epic masterpiece would do well to pick up Seal’s book and read it through before rewatching The Godfather. Anyone who ventures to watch the film for the first time should also pick up a copy of the book to learn the backstory of how the masterpiece came together.

Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli does not demystify the awe and wonder, power and majesty, beauty and sublimity of The Godfather. It adds to it. After all, we learn in Seal’s magisterial work that among the film’s most famous lines, “Leave the gun. Take the cannoli,” was ad-libbed. In reading this book, and as a longtime lover of the film since first watching it as a teenager, “I was blown away.”

Paul Krause is the editor-in-chief of VoegelinView. He is the author of The Odyssey of Love: A Christian Guide to the Great Books (Wipf and Stock, 2021) and contributed to The College Lecture Today (Lexington Press, 2019).

Support The University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!