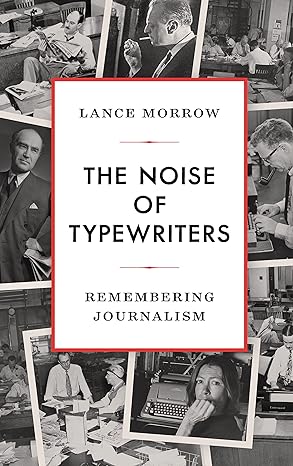

By Lance Morrow.

Encounter Books, 2023.

Hardcover, 200 pages, $27.99.

Reviewed by Alexander J. Fezza.

It is easier to describe The Noise of Typewriters by Lance Morrow by what it is not rather than what it is.

This book tells the story of journalism in the twentieth century, but unlike many other works that have ventured to do the same, it is neither chronological nor overly sentimental or self-serious. And yet, it is still a powerful and even romantic portrayal of this bygone era.

The Noise of Typewriters is defined by its organizational structure—or lack thereof. With its short, punchy chapters that jump between decades (and sometimes centuries and continents) seemingly at random, Morrow’s book can sometimes read like the scattered notes of Friedrich Nietzsche: simultaneously succinct and ambitious in scope. Each chapter is an unnamed and incredibly short profile of a different writer, ranging between three and ten pages.

The book is not a comprehensive history of twentieth century journalism, nor is it trying to be. It is a cross-section of Morrow’s memory. Its primary goal is to show that journalism is a thing of great import and beauty. Upon closing the book, one is inspired to delve into the field’s history further.

Morrow knows interesting figures (from the medieval Japanese monk Kenko to the snobbish socialite Henry “Chips” Channon), he knows precisely what is interesting about them in the context of his book’s broader themes, and he knows when to start and stop telling their stories. Morrow does not meander through the historical anecdotes he has selected; he is on a mission. This keen ability to balance brevity and compelling detail (what Morrow calls “narrative specificity”) betrays his past as a seasoned journalist before he ever explicitly mentions it.

The only thing that feels lacking in this book is a dive into the specifics of Morrow’s journalistic work. Through his time at TIME magazine and the now-defunct Washington Star, Morrow was an indelible part of twentieth century journalism in his own right. Yet, the only deep glimpse Morrow grants the reader is his reporting at the scene of the Mary Pinchot Meyer murder. Perhaps, forgivably, this is Morrow’s humility at play.

While the writer profiled in each chapter varies unpredictably, the figure that appears by far the most and looms over the book is TIME co-founder Henry Luce. Morrow does not narrativize in terms of broad historical eras such as “New Journalism” or even in terms of technological developments in the field. Rather, he seems to be a proponent of the great man theory of history. Morrow asserts that Henry Luce, through his power of will, changed the face of journalism and thus the face of America. And Morrow is incredibly convincing.

Morrow has an unwavering fascination with Luce’s reserved personality, his genius business sense, and his intuition for geopolitics. Even Luce’s faults, namely his penchant for grandiose theorizing (such as the idea that the twentieth century would be the “American Century”), are presented by Morrow as endearing. This makes sense, given that Morrow seems to share this tendency toward Big Ideas. He follows in the footsteps of Luce by giving the twentieth century a shape and a mythical character.

Morrow does not rigidly separate different mediums of expression, as many historians of journalism are wont to do. He enthusiastically acknowledges the way in which the story and self-representation of the twentieth century was a dialogue between print and sensory media (newspaper, magazines, film, and popular music). Morrow embodies this interplay in his analysis. He connects Henry Luce to Citizen Kane. He connects Graham Greene to Full Metal Jacket and The Rolling Stones.

The contemporary vision of journalism, especially among the writer-activist class at universities, has been reduced to the mantra of “speaking truth to power.” This loaded framing seems to have become detached from any sense of humility or real reverence for truth.

Humility is important for Morrow. Having grown up in the media and political hotbed of Washington D.C., he knows that narcissism is a nasty drug. Morrow writes admirably of the early twentieth century journalists who would not even think to call themselves “journalists,” as the term would have seemed far too highbrow. They instead opted for the term “reporters.” You would have been unlikely to find these men parroting the phrase “speaking truth to power.”

Notably, Morrow’s muse, Henry Luce, was power. Presidents waited with bated breath to read TIME’s Washington reporting, knowing that the newsmagazine was destined to inform public opinion. And yet, despite power’s well-known ability to corrupt, Morrow shows how Luce consistently painted a more truthful picture of the world than most of his less-influential enemies, teeming with ressentiment. Was Luce’s motivation “speaking truth to power”? Not quite—Luce and his team aimed at truth from a position of power, and whether or not this effort seemed to support the dominant power structures was a secondary concern.

Morrow is concerned with the journalist as a storyteller. He does not demand that journalists “speak truth to power,” but that they speak truth powerfully.

Morrow writes about the twentieth century with affection, but realistic distance. His evaluation of journalists of the time is not uniformly positive. He is quick to point out the era’s great failures, such as Walter Duranty (who failed to report on Stalin’s Holodomor while stationed in the USSR for The New York Times), as well as the flaws in great journalists, such as the black-and-white moral rigidity of Luce.

He is clear in revealing the perennial perils of journalism which are rooted in man’s fallen nature, such as the tendency of reporters to indulgently mold stories to suit their prefabricated narratives. Morrow respectably avoids this trap himself. He does not expound beyond his qualifications. Morrow personally knew many of the writers he mentions, but some he did not know well at all. Perhaps this is why his chapters are so short: he refuses to enter the “zone of fabulation” in lieu of “Being There.” (“Zone of fabulation” and “Being There” are among the many journalism terms that Morrow skillfully employs to invite the reader into his milieu.)

Even as Morrow acknowledges twentieth century journalism’s shortcomings, romantic descriptions of the time shine through. This is obvious enough from the book’s title: The Noise of Typewriters.

Morrow describes journalism in theological terms. He calls the “Ching!” of the typewriter “vaguely sacramental” and writes that he saw journalism as “sacred work.” For Morrow, humility in journalism is a virtue not for its own sake, but in service of piety. He demonstrates how Luce, with his grand theorizing, was striving—albeit imperfectly, humanly—toward God. Striving is part of the essence of good journalism.

Morrow believes in such a thing as objective truth and the unfolding of history—not a simplistic view of history as constant progress or increasing decadence, but a nuanced appreciation of the world’s ever-growing complexity. In The Noise of Typewriters, Morrow strives to reanimate the twentieth century in all of its complexity, and he succeeds.

At times, one can not help but wish that we were still in the age of twentieth century journalism, with its alcoholic, intrepid reporters hacking away at typewriters, coating their surroundings with crumpled papers while in pursuit of the perfect story. The Noise of Typewriters illustrates the intoxicating intrigue and allure of this long-lost world.

In our narcissistic Twitter age, journalism has lost its mystique. This book chronicles an era when the power of writing and ideas was more separate from the self-aware, egoic forces that now dominate. Prose in journalism was an opportunity for the human spirit to shine through the written word. It still is, though excessive noise and cheap clickbait in the contemporary media landscape can obscure this.

There are practical reasons to miss the typewriter, besides merely its aesthetic and nostalgic appeal. Morrow notes that the constant retyping that one must undertake due to spelling and grammatical errors encourages arduous rewriting of material. He masterfully describes the physicality of sessions with the typewriter. Some of it is relatable to the contemporary experience of laptop writing, but much of it is not.

Computers simply do not seem quite as beautiful as typewriters. Yet, perhaps this view is tainted by a lack of hindsight. Morrow repeatedly notes that the past is easier to evaluate than the present. Perhaps, decades from now, currently unimaginable technologies will retrospectively make the era of early twenty-first century journalism—with its glass-skyscraper newsrooms, Twittersphere, and modern, razor-thin computers—romantic. Then someone with Morrow’s wit, if there are any left, can write The Noise of Laptops.

Alexander J. Fezza is a writer and filmmaker in the Philadelphia area who studied Humanities and Communication at Villanova University.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!