Edited by Bill Meehan.

Encounter Books, 2023.

Hardcover, 464 pages, $39.99.

Reviewed by Mark G. Brennan.

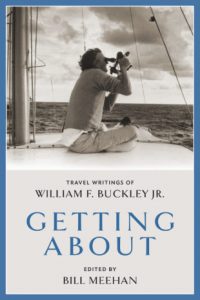

What better time to dive into a compilation of travel essays than the summer travel season? Editor Bill Meehan has culled from William F. Buckley, Jr.’s voluminous writings between 1958 and 2004 about vacations—or what Winston Churchill dismissed as “doing something else”—to teach those who didn’t already know that Buckley “was constantly in motion.” For most Americans, summer vacation means lazing on a beach, camping in a park, or perfecting a golf swing. Buckley’s vacations, not limited to summer, were indeed “something else.” His travels literally spanned the globe. Sailboats and supersonic jets provided his transport. And he toured with names you will recognize but have trouble remembering as Meehan’s selections will remind you.

Encounter Books deserves credit for adding this work to the comprehensive bibliography Meehan has worked on at Buckley’s request since a fortuitous 1995 interview. Until (or is it if?) Sam Tanenhaus eventually proves otherwise, Meehan stands as the foremost scholarly authority on Buckley and his work. He has taught seminars about Buckley, catalogued his 5,000 volume personal library, and written reviews and articles on Buckley’s life and career. Needless to say, Meehan knows his way around the Buckley corpus. This volume’s curation stands as proof of Meehan’s unique knowledge and first-rate connoisseurship. Buckley’s diehard fans will want to add it to their bookshelves.

Let’s dispense with the sine qua non of a Buckley book review: the reviewer’s mention of Buckley’s sesquipedalian proclivities, as Buckley himself might have put it. Yes, this reviewer, an armchair etymologist, interrupted his reading to look up aposiopesis, cabotage, and levanter. And no, I don’t remember what any of them mean. But my reward will come the next time I read Buckley and I can at least say, “I think I’ve seen that word before.” In the meantime, I can’t wait to return to the classroom this September to try out “cupcakeable” on my undergrads. Buckley’s usage in relation to “the feel of the wind” provided little context as to its meaning. And I could only find an unrelated definition at a sketchy website called “Urban Dictionary.” So I’m not sure if I’ll be met with blank stares from my students or a visit from NYU’s Bias Response Team. If the latter, I may find myself “doing something else” professionally.

Additional hurdles aside from obscure words may annoy those not predisposed to Buckley’s writing style. Sailing across the sea provides lots of time for navel gazing, and writing about it. Readers who don’t travel by yacht will want to skim much of Buckley’s thalassophilic ruminations that relate to boatmanship. Here Meehan might have employed ellipses to lighten the volume both figuratively and physically. I longed for a word I didn’t know after slogging through sentences like this one that Buckley might just as well have lifted from an instruction manual: “We examined the shaft and found that a stainless-steel through-pin binding the shaft to the engine had sheared, and that moreover the liberated member had rocketed aft, imbedding the propeller in the sternpost forward of the rudder.” I’m pretty sure that’s a problem. Then again, I’m the guy whose frustrated wife mockingly chants “Rightey-tighty and lefty-loosey” as a reminder anytime I dig through our—OK, her—tool drawer. Less mechanically-inclined readers will find WFB’s aeronautic adventures more edifying.

Humor born of frustration suffuses the pieces. It wasn’t that long ago that no one carried along a mechanical writing contrivance, like a laptop, while traveling. We didn’t feel like we were missing anything because they didn’t exist. Yet long before their advent, Buckley complained in one 1978 syndicated column about lugging “two bags, a briefcase, and a typewriter,” all of which turned his Amtrak jaunt from New York to Washington into “an Alpine experience.” Typewriters and their awkward heft provided much fodder for Buckley’s humor in the pre-laptop era. Let us hope the book’s second edition includes the word in its index.

Compilations allow readers to make connections they would not otherwise make when reading articles contemporaneously. One comes away from this text thinking Buckley suffered from an Ahabesque obsession with airline luggage surcharges. Closer inspection reveals that his complaints came at multi-year intervals, not the quick succession presented in the book. The regulatory environment hamstringing his air travel starting in the 1960s also ignited his inner free marketeer. If you bristle while awaiting your mandatory turn in the TSA’s kabuki inspection theater, wait till you read his probabilistic dissection of airport security in his November 2001 “Security in the Air,” just weeks after 9/11. Oddly enough, his next essay makes amends with big government intrusions when he argues for railroad subsidies as “economically defensible, culturally desirable, and tangentially useful to the common defense.”

Getting About provides a soothing respite from our iPhone-addled daily existence. If you find yourself doom scrolling for hours or jumping at every alert on your phone, Buckley’s half-century of globe-trotting reminiscences will soothe your 2023-itis. Most of us can’t afford to charter sailboats for half-day cruises, let alone for ocean crossings. But we can now enjoy the peace of mind they provide as channeled through Buckley’s observations. Before technology turbocharged our lives, Buckley noted in 1995 that “everyday life moves fast.” However, he learned that “a sailboat forces you to slow down” after years on the briny. His long-form seaborne musings, even including the instruction manual stuff, promote a sense of inner peace your iPhone never will, regardless of how many meditation apps you download.

Meehan expertly ends the collection on a bittersweet coda with a 2004 piece from The Atlantic, just four years before Buckley’s death. Buckley’s allusions to life’s finality seep through as he rationalizes his decision to sell his last sailboat, Patito. He recalls good times long past enjoying meals with other sailors, snug “in your secure little anchorage.” After a life toiling for pleasure at sea, Buckley recalled those peaceful moments harborside as “a compound of life’s social pleasures in the womb of nature.” His final goodbye to Patito means he must “forfeit all that is not lightly done.” In landlubbers’ lingo, Buckley’s life has little meaning without challenges and trials, like those he encountered crossing the seas and writing about the accomplishment. Buckley sadly yet correctly foresaw his last four years of post-Patito existence—free of the mechanical, nautical, and financial inconveniences boats impose—as his final earthly step before “giving up life itself.”

Mark G. Brennan lives in Manhattan and teaches at New York University.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!